This blog is not peer reviewed at all. I write it, I put it out there, and people read it or not. It is my little megaphone that I alone control.

But I don’t think anyone, or at least I hope that no-one, thinks that I am publishing scientific papers here. They are my opinion pieces, and only worthwhile if there are people who have found my previous opinions to have turned out to be right in some way.

There has been a lot of discussion recently about peer review. This post is to share some of my experiences with peer review, both as an author and as an editor, from three decades ago.

In my opinion peer review is far from perfect. But with determination new and revolutionary ideas can get through the peer review process, though it may take some years. The problem is, of course, that most revolutionary ideas are wrong, so peer review tends to stomp hard on all of them. The alternative is to have everyone self publish and that is what is happening with the arXiv distribution service. Papers are getting posted there with no intent of ever undergoing peer review, and so they are effectively getting published with no review. This can be seen as part of the problem of populism where all self proclaimed experts are listened to with equal authority, and so there is no longer any expertise.

My Experience with Peer Review as an Author

I have been struggling with a discomfort about where the herd has been headed in both Artificial Intelligence (AI) and neuroscience since the summer of 1984. This was a time between my first faculty job at Stanford and my long term faculty position at MIT. I am still concerned and I am busy writing a longish technical book on the subject–publishing something as a book gets around the need for full peer review, by the way…

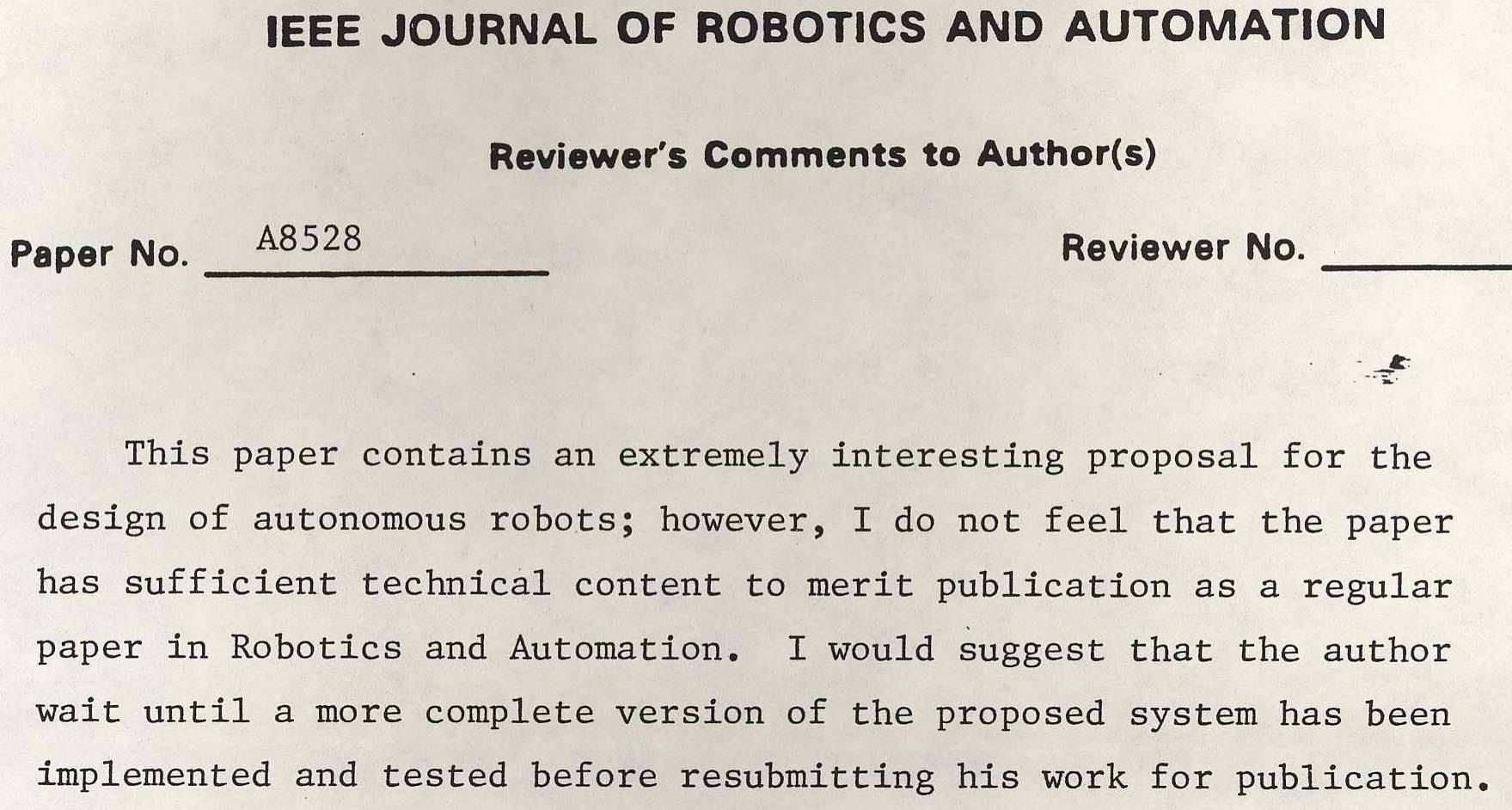

When I got to MIT in the fall of 1984 I shifted my research based on my concerns. A year later I was ready to talk about the what I was doing, and submitted a journal paper describing the technical idea and an initial implementation. Here is one of the two reviews.

It was encouraging, but both it and a second review recommended that the paper not be published. That would have been my first rejection. However, the editor, George Bekey, decided to publish it anyway, and it appeared as:

Brooks, R. A. “A Robust Layered Control System for a Mobile Robot“, IEEE Journal of Robotics and Automation, Vol. 2, No. 1, March 1986, pp. 14–23; also MIT AI Memo 864, September 1985.

Google Scholar reports just under 12,000 citations of this paper, my most cited paper ever. The approach to controlling robots, the subsumption architecture that it proposed led directly to the Roomba, a robot vacuum cleaner, which with over 30 million sold is the most produced robot ever. Furthermore the control architecture was formalized over the years by a series of researchers, and its descendant, behavior trees, is now the basis for most video games. (Both Unity and Unreal use behavior trees to specify behavior.) The paper still has multi billion dollar impact every year.

Most researchers who stray, believing the herd is wrong, end up heading off in their own wrong direction. I was extraordinarily lucky to choose a direction that has had incredible practical impact.

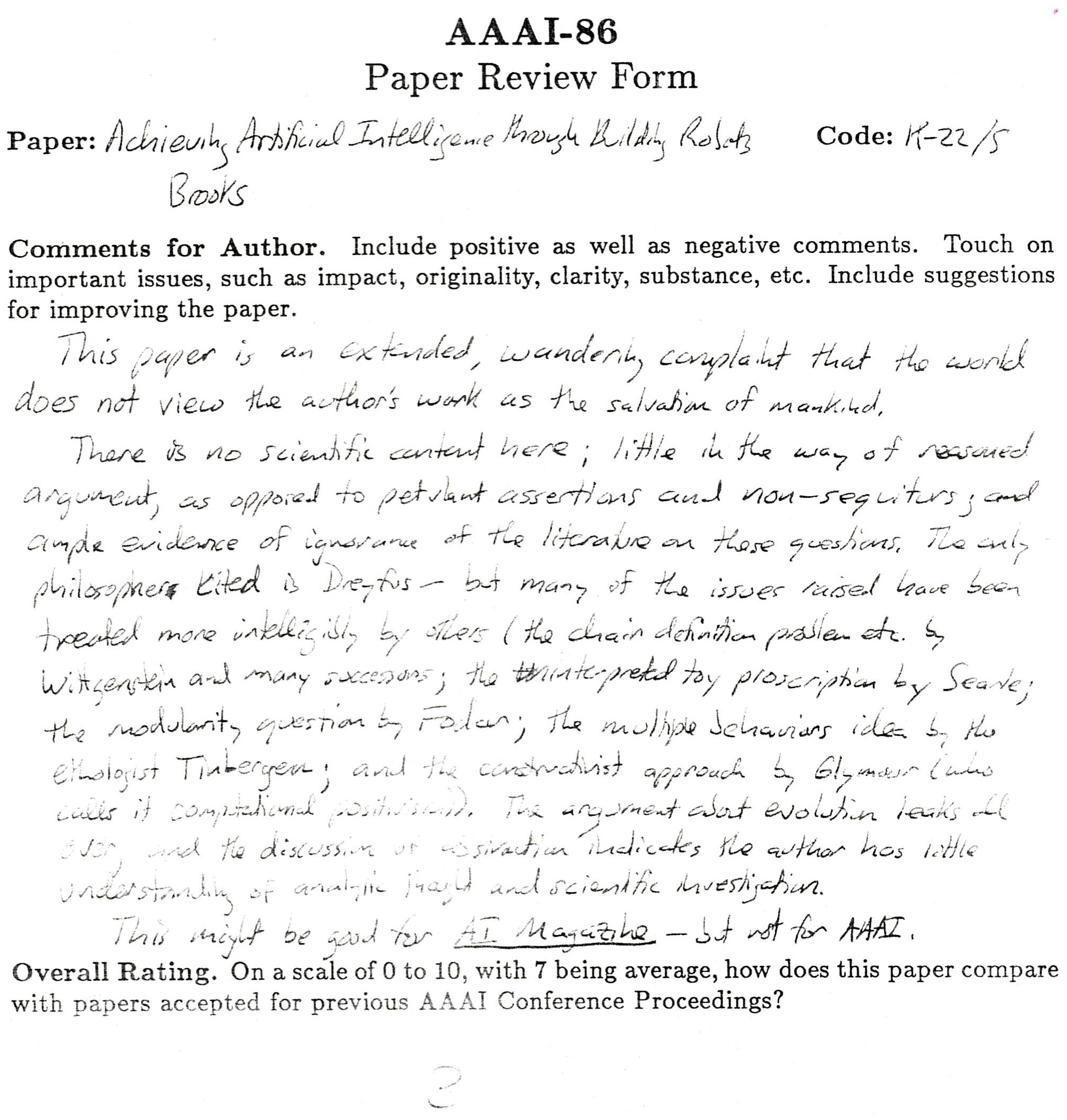

However, I was worried at a deeper intellectual level, and so almost simultaneously started writing about the philosophical underpinnings of research in AI, and how my approach differed. There the reviews were more brutal, as is shown in a review here:

This was a a review of lab memo AIM-899, Achieving Artificial Intelligence through Building Robots which I had submitted to a conference.This paper was the first place that I talked about the possibility of robot vacuum cleaners as an example of how the philosophical approach I was advocating could lead to new practical results.

The review may be a little hard to read in the image above. It says:

This paper is an extended, wandering complaint that the world does not view the author’s work as the salvation of mankind.

There is no scientific content here; little in the way of reasoned argument, as opposed to petulant assertions and non-sequiturs; and ample evidence of ignorance of the literature on these questions. The only philosopher cited is Dreyfus–but many of the issues raised have been treated more intelligibly by others (the chair definition problem etc. by Wittgenstein and many successors; the interpreted toy proscription by Searle; the modularity question by Fodor; the multiple behaviors ideas by Tinbergen; and the constructivist approach by Glymour (who calls it computational positivism). The argument about evolution leaks all over, and the discussion on abstraction indicates the author has little understanding of analytic thought and scientific investigation.

Ouch! This was like waving a red flag at a bull. I posted this and other negative reviews on my office door where they stayed for many years. By June of the next year I had added to it substantially, and removed the vacuum cleaner idea, but kept in all the things that the reviewer did not like, and provocatively retitled it Intelligence Without Representation. I submitted the paper to journals and got further rejections–more posts for my door. Eventually its fame had spread to the point that the Artificial Intelligence Journal, the mainstream journal of the field, published it unchanged (Artificial Intelligence Journal (47), 1991, pp. 139–159) and it now has 6,900 citations. I outlasted the criticism and got published.

That same year at the major international conference IJCAI: International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence I was honored to win the Computers and Thought award, quite a surprise to me, and I think to just about every one else. With that honor came an invitation to have a paper in the proceedings without the six page limit that applied to everyone else, and without the peer review process that applied to everyone else. My article was twenty seven pages long, double column, a critical review article of the history of AI, also with a provocative and complementary title, Intelligence Without Reason, (Proceedings of 12th Int. Joint Conf. on Artificial Intelligence, Sydney, Australia, August 1991, pp. 569–595). It now has over 3,100 citations.

My three most cited papers were either rejected under peer review or accepted with no peer review. So I am not exactly a poster child for peer reviewed papers.

My Experience With Peer Review As an Editor

In 1987 I co-founded a journal, the International Journal of Computer Vision. It was published by Kluwer as a hardcopy journal for many years, but now it is run by Springer and is totally online. It is now in its 128th volume, and has had many hundreds of issues. I co-edited the first seven volumes which together had a total of twenty eight issues.

The journal has a very strong reputation and consistently ranks in the top handful of places to publish in computer vision, itself a very hot topic of research today.

As an editor I soon learned a lot of things.

- If a paper was purely theoretical with lots of equations and no experiments involving processing an image it was much more likely to get accepted than a paper which did have experimental results. I attributed this to people being unduly impressed by mathematics (I had a degree in pure mathematics and was not as easily impressed by equations and complex notation). I suspected that many times the reviewers did not fully read and understand the mathematics as many of them had very few comments about the contents of such papers. If, however, a paper had experiments with real images (and back then computers were so slow it was rarely more than a handful of images that had been processed), the same reviewers would pick apart the output, faulting it for not being as good as they thought it should be.

- I soon learned that one particular reviewer would always read the mathematics in detail, and would always find things to critique about the more mathematical papers. This seemed good. Real peer review. But soon I realized that he would always recommend rejection. No paper was ever up to his standard. Reject! There were other frequent rejecters, but none as dogmatic as this particular one.

- Likewise I found certain reviewers would always say accept. Now it was just a matter of me picking the right three referees for almost any paper and I could know whether the majority of reviewers would recommend acceptance or rejection before I had even sent the paper off to be reviewed. Not so good.

- I came to realize that the editor’s job was real, and it required me to deeply understand the topic of the paper, and the biases of the reviewers, and not to treat the referees as having the right to determine the fate of the paper themselves. As an editor I had to add judgement to the process at many steps along the way, and to strive for the process to improve the papers, but also to let in ideas that were new. I now came to understand George Bekey and his role in my paper from just a couple of years before.

Peer reviewing and editing is a lot more like the process of one on one teaching than it is of processing the results of a multiple choice exam. When done right it is about coaxing the best out of scientists, and encouraging new ideas to flourish and the field to proceed.

The UPSHOT?

Those who think that peer review is inherently fair and accurate are wrong. Those who think that peer review necessarily suppresses their brilliant new ideas are wrong. It is much more than those two simple opposing tendencies.

Peer review grew up in a world where there were many fewer people engaging in science than today. Typically an editor would know everyone in the world who had contributed to the field in the past, and would have enough time to understand the ideas of each new entrant to the field as they started to submit papers. It relied on personal connections and deep and thoughtful understanding.

That has changed just due to the scale of the scientific endeavor today, and is no longer possible in that form.

There is a clamor for double blind anonymous review, in the belief that that produces a level playing field. While in some sense that is true, it also reduces the capacity for the nurturing of new ideas. Clamorers need to be careful what they wish for–metaphorically it reduces them to competing in a speed trial, rather than being appreciated for virtuosity. What they get in return for zeroing the risk of being rejected on the basis of their past history or which institution they are from is that they are condemned to forever aiming their papers at the middle of a field of mediocrity, with little chance for achieving greatness.

Another factor is that the number of new journals has changed. Institutions, and sometimes whole countries, decide that the way for them to get a better name for themselves is to have a scientific journal, or thirty. They set them up and put one of their local people who has no real understanding of the flow of ideas in the particular field at the global scale, as editor. Now editing becomes a mechanical process, with no understanding of the content of the paper or the qualifications of who they ask to do the reviews. I know this to be true as I regularly get asked to review papers in fields in which I have absolutely no knowledge, by journal editors that I have never heard of, nor of their journal, nor its history. I have been invited to submit a review that can not possibly be a good review. I must induce that other reviews may also not be very good.

I don’t have a solution, but I hope my observations here might be interesting to some.

Peer review is valid for minor, incremental advances in AI, but not for major leaps.

~~ Peer review ~~

In this blog post the author attacks the traditional model of peer review for publishing scientific research.

* Peer review has flaws: potentially groundbreaking work is rejected, editors can bias the likelihood of a paper’s acceptance, trend to accept theoretical work with lots of (possibly wrong) math and reject work with experiments since the output was deemed not good enough.

* Peer review model emerged when there were fewer participants and ideas. Today, the scale, speed, and overcrowding of new journals, and double blind review process offers less of an opportunity for new ideas and moves our field toward mediocrity.

* Peer review needs an update, but should not get rejected entirely. No solution is provided.

Overall, I liked this blog post. I found it engaging and the anecdotes interesting and humorous. In particular, the cutting language of the 80s reviewer “petulant assertions and non-sequiturs” gives us all something to aspire to. I don’t think the idea peer review needs an update is original, but the author’s comments on editor impact on peer review were novel (for me).

Some negative aspects of this blog post: it doesn’t address some of the recent updates for paper review in various CS communities. The arguments on double-blind don’t hold very well in the robotics field– it’s often very easy to tell which lab a paper is coming from based on the robot/problem formulation. It’s unclear to me why we should allow virtuosity for paper acceptance.

**strong accept**

Numerical score:

– originality (7/10)

– technical quality (5/10)

– significance (10/10)

– relevance (10/10)

– quality of writing (9/10)

– overall score (9/10)

Well played, sir. 🙂

“toy poscription” clearly was proscription, and while it sounds strange, the word toy comes directly from the paper being reviewed.

Thanks. I’ve updated the post.

I appreciate the balance that you have injected into this piece. The peer review process can be subverted or abused intentionally or unintentionally, but it can also work very effectively. While modern editors can no longer have personal knowledge of all experts, even in modestly sized fields, they can often call upon associate or section editors to help them broaden their reach. Editorship is frequently as much about teaching as adjudicating, but this means that those who strive for excellence as active participants in the process – as authors, reviewers, or editors – can refine their own critical thinking, evaluation, and writing skills in addition to helping to bring the best scientific product to the community. This is an effort worthy of nurturing, helping to build the historical record of our endeavors. Thanks for keeping the discussion personal.

Maybe there should be an explicit “Fringe AI” conference where the acceptance criterion is an intriguing idea or a cool demo. These would be fun to attend.

Robotics might be a relatively benign field.

Papers on Alzheimer’s Disease that offer evidence for causes not related to amyloid plaques or tau proteins are, I gather, usually rejected out of hand. In public discussions, someone always cites funding they consider woefully inadequate, that must therefore be directed solely to interfering with plaque or tangle formation, so as not to go entirely to waste. It makes me wonder what the generations of amyloid researchers will do if it is finally demonstrated that interfering with amyloid or tau production is a dead end. Will there still be amyloid journals with amyloid reviewers of amyloid papers, and amyloid grants awarded according to the instincts of amyloid chairs?

As an outsider, it makes me think of the predicament of early perceptron researchers, and of AI winter.

Peer review (especially when overseen by active and intelligent editors) is better than none (as this “epidemic” of covid19 preprints shows). However, there may be better architectures or algorithms for it. Some possibilities: getting conference reviewers to rank rather than score submissions and then combine these, the EU experimented with automatically eliminating the best and worst reviews and keeping the others (which provides motivation not to hype or damn in reviews). This needs studying and modelling (fortunately this work is beginning).

One idea is to accept all reasonably written paper. Now since most journals have electronic versions, page limit should not be a problem any more. Time will eventually throw away the trash and liées the gold.

It sounds like you found that the peer review process has very high bias and very high variance. Reviewers come into each review with pre-conceived notions of what the outcome will be, and the outcome of each review varies highly with factors independent of the paper under review. I imagine that:

– The bias would be fine if it were aligned with reality, but the fact that the biases of each reviewer lead to such disparate results suggests that biases do not align with reality for too many reviewers.

– The variance would be fine if you could get enough reviewers, but this is clearly not feasible.

It’s an interesting problem, and I’m curious to hear more about your experiences trying to address it in IJCV’s peer-review processes. Specifically:

– What did you try to make paper outcomes more consistent?

– Did you find any effective way to get reviewers to review equations and experiments more for their merits than for their opaqueness or transparency?

– Were you able to figure out why reviewers’ judgments were so poorly aligned with yours?

I’ll note that there do seem to be some perverse incentives when authors present opaque equations or easily-digestible experimental results. If reviewers tend towards looking for reasons to reject a paper, then authors are incentivized to make their papers more opaque. Any transparency is a chance for a reviewer to criticize and reject a paper. On the other hand, if reviewers tend towards looking for reasons to accept a paper, authors are incentivized to make their papers more transparent. Consequently, it’s “wrong” in some sense to think of reviewers as gatekeepers since doing so leads to the “bad end” with perverse incentives. It would be better to think of reviewers as signal boosters for good papers since that leads to the good end. It’s unfortunate that the common perception leads to the “bad end.”

I suspect the signal boosting approach was more common in the academic past. I wonder when (and how) the gatekeeping approach became more dominant.

Cheers,

-eqs

I do a lot of reviewing and used to be editor chief of an Elsevier Journal. I guess I agree with much of the criticism posted above, yet the process (in my experience) usually led to improvements in papers because constructive reviews add value. The nonsensical polemics in the unfiltered blogpost type “journals” is not so easy to dismiss.

At the time when some publishers were being heavily criticised for the charges they made by the Economist, I wrote to that newspaper comparing the quality of letters in the print version (which are “reviewed” by an editor) with the nonsense that appeared in the unedited web comments. That letter was promptly published by the letters editor, demonstrating high critical appreciation.

” I suspected that many times the reviewers did not fully read and understand the mathematics as many of them had very few comments about the contents of such papers.”

I am nodding my head off with this one in agreement. That is my number 1 issue with the quality of reviewer feedback. In my field (automatic control) the math (or shall we say, the symbolic manipulation) can get quite heavy, so a reviewer may “check the syntax” (the least we could ask for!) without thoroughly parsing the semantics of the paper. That also reduces the chances of providing constructive comments for enhancing the readability of papers.

I have encountered reviewers who exploit the process as a way to acquire citations for their own work. They would suggest a couple of references for the author to consult, and at least one of these would invariably be authored by the reviewer. In a vain attempt to make it less blatant, they leave out the authors of those references. Doesn’t make a difference!

I think we should think really hard about the whole peer review ‘ecosystem’. Perhaps reviewers should be paid. If not cash then credits for buying books? Maybe let the social scientists experiment on us…

PS. Been waiting for a “longish technical book” from you for a long time. Hope to read it soon 🙂

COVID-19 is helping with the writing. But the project keeps getting bigger and bigger the more I explore. That said, I am churning out carefully researched and edit paragraphs (sometimes running to pages) every day.

I’ve had some great experience having my papers refereed. I remember when I was a grad student being annoyed at referees not “getting” one of my papers, but then I realized that my writing was confusing and had room to improve. It was a really good lesson that even when the referee is confused, they were confused by _my_ paper, and so I should probably do a better job.

Someone, I don’t remember who, recently suggested that people can irrevocably add their names to a paper. The first names will be authors. Then when it’s public, anyone can add his/her name to the paper. This will then be findable and easily cross-referenceable against other lists, like retracted papers, etc. This seems interesting. There is some incentive to participate in this scheme. I wonder if there could be an even better scheme with better incentives.