Nothing is ever as good as it first seems and nothing is ever as bad as it first seems.

— A best memory paraphrase of advice given to me by Vice Admiral Joe Dyer, former chief test pilot of the US Navy and former Commander of NAVAIR.

[You can follow me on social media: @rodneyabrooks.bsky.social and see my publications etc., at https://people.csail.mit.edu/brooks]

Table of contents

Introduction

What I Nearly Got Wrong

What Has Surprised Me, And That I Missed 8 Years Ago

My Color Scheme and Past Analysis

My New Predictions

Quantum Computers

Self Driving Cars

Humanoid Robots

Neural Computation

LLMs

Self Driving Cars

A Brief Recap of what "Self Driving" Cars Means and Meant

My Own Experiences with Waymo in 2025

Self Driving Taxi Services

__Cruise

__Tesla

__Waymo

__Zoox

Electric Cars

Flying Cars

Robotics, AI, and Machine Learning

Capabilities and Competences

World Models

Situatedness vs Embodiment

Dexterous Hands

Human Space Flight

Orbital Crewed Flights

Suborbital Crewed Flights

Boeing's Starliner

SpaceX Falcon 9

NASA, Artemis, and Returning to the Moon

SpaceX Starship

Blue Origin Gets to Orbit

New Space Stations

Addendum

Introduction

This is my eighth annual update on how my dated predictions from January 1st, 2018 concerning (1) self driving cars, (2) robotics, AI , and machine learning, and (3) human space travel, have held up. I promised then to review them at the start of the year every year until 2050 (right after my 95th birthday), thirty two years in total. The idea was to hold myself accountable for those predictions. How right or wrong was I?

The summary is that my predictions held up pretty well, though overall I was a little too optimistic. That is a little ironic, as I think that many people who read my predictions back on January 1st, 2018 thought that I was very pessimistic compared to the then zeitgeist. I prefer to think of myself as being a realist.

And did I see LLMs coming? No and yes. Yes, I did say that something new and big that everyone accepted as the new and big thing in AI would come along no earlier than 2023, and that the key paper for its success had already been written by before I made my first predictions. And indeed LLMs were generally accepted as the next big thing in 2023 (I was lucky on that date), and the key paper, Attention Is All You Need, was indeed already written, and had first appeared in June of 2017. I wrote about this extensively in last year’s scorecard. But no, I had no idea it would be LLMs at the time of my correct prediction that something big would appear. And that lack of specificity on the details of exactly what will be invented and when is the case with all my predictions from the first day of 2018.

I did not claim to be clairvoyant about exactly what would happen, rather I was making predictions about the speed of new research ideas, the speed of hype generation, the speed of large scale deployments of new technologies, and the speed of fundamental changes propagating through the world’s economy. Those speeds are very different and driven by very different realities. I think that many people get confused by that and make the mistake of jumping between those domains of reality, thinking all the speeds will be the same. In my case my estimates of those speeds are informed by watching AI and robotics professionally, for 42 years at the time of my predictions. I became a graduate student in Artificial Intelligence in January of 1976, just shy of 20 years after the initial public outing of the term Artificial Intelligence at the summer workshop in 1956 at Dartmouth. And now as of today I have been in that field for 50 years.

I promised to track my predictions made eight years ago today for 32 years. So I am one quarter of the way there. But the density of specific years of events or marking percentages of adoption that I predicted start to fall off right around now.

Sometime during 2026 I will bundle up all my comments over the eight years specifically mentioning years that have now passed, and put them in an archival mid-year post. Then I will get rid of the three big long tables that dominate the body of this annual post, and have short updates on the sparse dates for the next 24 years.

I will continue to summarize what has happened in self-driving cars generally, including electrification progress and the forever promised flying cars, along with AI and robotics, and human space flight. But early in 2025 I made five new predictions for the coming ten years, without specific dates, but which summarize what I think will happen. I will track these predictions too.

What I Nearly Got Wrong

The day before my original prediction post in 2018 the price of Bitcoin had opened at $12,897.70 and topped out at $14,377.40 and 2017 had been the first year it had ever traded at over $1,000. The price seemed insane to me as Bitcoin wasn’t being used for the task for which it had been designed. The price seemed to me then, and now, to be purely about speculation. I almost predicted when it would be priced at $200, on the way down. But, fortunately, I checked myself as I realized that the then current state of the market made no sense to me and so any future state may not either. Besides, I had no experience or expertise in crypto pricing. So I left that prediction out. I had no basis to make a prediction. That was a wise decision, and I revisit that reasoning as I make new predictions now, and implore myself to only make predictions in fields where I know something.

What Has Surprised Me, And That I Missed 8 Years Ago

I made some predictions about the future of SpaceX although I didn’t always label them as being about SpaceX. A number of my predictions were in response to pronouncements by the CEO of SpaceX. My predictions were much more measured and some might say even pessimistic. Those predictions so far have turned out to be more optimistic than how reality has unfolded.

I had made no specific predictions about Falcon 9, though I did make predictions about the subsequent SpaceX launch family, now called Starship, but then known as BFR, which eight years later has not gotten into orbit.

In the meantime SpaceX has scaled the Falcon 9 launch rate at a phenomenal speed, and the magnitude of the growth is very surprising.

Eight years ago, Falcon 9 had been launched 46 times, all successful, over the previous eight years, and it had recently had a long run of successful landings of the booster whenever attempted. At that time five launches had been on a previously used booster, but there had been no attempts to launch Falcon Heavy with its three boosters strapped together.

Now we are eight years on from those first eight years of Falcon 9 launches. The scale and success rate of the launches has made each individual launch an unremarkable event, with humans being launched a handful of times per year. Now the Falcon 9 score card stands at 582 launches with only one failed booster, and there have been 11 launches of the three booster Falcon Heavy, all successful. That is a sustained growth rate of 38% year over year for eight years. And that it is a very high sustained deployment growth rate for any complex technology.

There is no other modern rocket with such a volume of launches that comes even close to the Falcon 9 record. And I certainly did not foresee this volume of launches. About half the launches have had SpaceX itself as the customer, starting in February 2018, launching an enormous satellite constellation (about two thirds of all satellites ever orbited) to support Starlink bringing internet to everywhere on the surface of Earth.

But… there is one historical rocket, a suborbital one which has a much higher record of use than Falcon 9 over a much briefer period. The German V-2 was the first rocket to fly above the atmosphere and the first ballistic missile to be used to deliver bombs. It was fueled with ethanol and liquid oxygen, and was steered by an analog computer that also received inputs from radio guide signals–it was the first operational liquid fueled rocket. It was developed in Germany in the early 1940’s and after more than a thousand test launches was first put into operation on September 7th, 1944, landing a bomb on Paris less than two weeks after the Allied liberation of that city. In the remaining 8 months of the war 3,172 armed V-2 rockets were launched at targets in five countries — 1,358 were targeted at London alone.

My Color Scheme and Past Analysis

The acronyms I used for predictions in my original post were as follows.

NET year means it will not happen before that year (No Earlier Than)

BY year means I predict that it will happen by that year.

NIML, Not In My Lifetime, i.e., not before 2050.

As time passes mentioned years I color then as accurate, too pessimistic, or too optimistic.

Last year I added hemming and hawing. This is for when something looks just like what I said would take a lot longer has happened, but the underlying achievement is not what everyone expected, and is not what was delivered. This is mostly for things that were talked about as being likely to happen with no human intervention and it now appears to happen that way, but in reality there are humans in the loop that the companies never disclose. So the technology that was promised to be delivered hasn’t actually been delivered but everyone thinks it has been.

When I quote myself I do so in orange, and when I quote others I do so in blue.

I have not changed any of the text of the first three columns of the prediction tables since their publication on the first day of 2018. I only change the text in the fourth column to say what actually happened. This meant that by four years ago that fourth column was getting very long and skinny, so I removed them and started with fresh comments two years ago. I have kept the last two year’s comments and added new ones, with yellow backgrounds, for this year, removing the yellow backgrounds from 2025 comments that were there last year. If you want to see the previous five years of comments you can go back to the 2023 scorecard.

My NEW PREDICTIONS

On March 26th I skeeted out five technology predictions, talking about developments over the next ten years through January 1st, 2036. Three weeks later I included them in a blog post. Here they are again.

1. Quantum Computers. The successful ones will emulate physical systems directly for specialized classes of problems rather than translating conventional general computation into quantum hardware. Think of them as 21st century analog computers. Impact will be on materials and physics computations.

2. Self Driving Cars. In the US the players that will determine whether self driving cars are successful or abandoned are #1 Waymo (Google) and #2 Zoox (Amazon). No one else matters. The key metric will be human intervention rate as that will determine profitability.

3. Humanoid Robots. Deployable dexterity will remain pathetic compared to human hands beyond 2036. Without new types of mechanical systems walking humanoids will remain too unsafe to be in close proximity to real humans.

4. Neural Computation. There will be small and impactful academic forays into neuralish systems that are well beyond the linear threshold systems, developed by 1960, that are the foundation of recent successes. Clear winners will not yet emerge by 2036 but there will be multiple candidates.

5. LLMs. LLMs that can explain which data led to what outputs will be key to non annoying/dangerous/stupid deployments. They will be surrounded by lots of mechanism to keep them boxed in, and those mechanisms, not yet invented for most applications, will be where the arms races occur.

These five predictions are specifically about what will happen in these five fields during the ten years from 2026 through 2035, inclusive. They are not saying when particular things will happen, rather they are saying whether or not certain things will happen in that decade. I will do my initial analysis of these five new predictions immediately below. For the next ten years I will expand on each of these reviews in this annual scorecard, along with reviews of my earlier predictions. The ten years for these predictions are up on January 1st, 2036. I will have just turned 81 years old then, so let’s see if I am still coherent enough to do this.

Quantum Computers

The successful ones will emulate physical systems directly for specialized classes of problems rather than translating conventional general computation into quantum hardware. Think of them as 21st century analog computers. Impact will be on materials and physics computations.

The original excitement about quantum computers was stimulated by a paper by Peter Shor in 1994 which gave a digital quantum algorithm to factor large integers much faster than a conventional digital computer. Factoring integers is often referred to as “the IFP” for the integer factorization problem.

So what? The excitement around this was based on how modern cryptography, which provides our basic security for on-line commerce, works under the hood.

Much of the internet’s security is based on it being hard to factor a large number. For instance in the RSA algorithm Alice tells everyone a large number (in different practical versions it has 1024, 2048, or 4096 bits) for which she knows its prime factors. But she tells people only the number not its factors. In fact she chose that number by multiplying together some very large prime numbers — very large prime numbers are fairly easy to generate (using the Miller-Rabin test). Anyone, usually known as Bob, can then use that number to encrypt a message intended for Alice. No one, neither Tom, Dick, nor Harry, can decrypt that message unless they can find the prime factors of Alice’s public number. But Alice knows them and can read the message intended only for her eyes.

So… if you could find prime factors of large numbers easily then the backbone of digital security would be broken. Much excitement!

Shor produced his algorithm in 1994. By the year 2001 a group at IBM had managed to find the prime factors of the number 15 using a digital quantum computer as published in Nature. All the prime factors. Both 3 and 5. Notice that 15 has only four bits, which is a lot smaller than the number of bits used in commercial RSA implementations, namely 1024, 2048, or 4096.

Surely things got better fast. By late 2024 the biggest numbers that had been factored by an actual digital quantum computer had 35 bits which allows for numbers no bigger than 34,359,738,367. That is way smaller than the size of the smallest numbers used in RSA applications. Nevertheless it does represent 31 doublings in magnitude of numbers factored in 23 years, so progress has been quite exponential. But it could take another 500 years of that particular version of exponential growth rate to get to conquering today’s smallest version of RSA digital security.

In the same report the authors say that a conventional, but very large computer (2,000 GPUs along with a JUWELS booster, which itself has 936 compute nodes each consisting of four NVIDIA A100 Tensor Core GPUs themselves each hosted by 48 dual threaded AMD EPYC Rome cores–that is quite a box of computing) simulating a quantum computer running Shor’s algorithm had factored a 39 bit number finding that 549,755,813,701 = 712,321 × 771,781, the product of two 20 bit prime numbers. That was its limit. Nevertheless, an actual digital quantum computer can still be outclassed by one simulated on conventional digital hardware.

The other early big excitement for digital quantum computers was Grover’s search algorithm, but work on that has not been as successful as for Shor’s IFP solution.

Digital quantum computation nirvana has not yet been demonstrated.

Digital quantum computers work a little like regular digital computers in that there is a control mechanism which drives the computer through a series of discrete steps. But today’s digital quantum computers suffer from accumulating errors in quantum bits. Shor’s algorithm assumes no such errors. There are techniques for correcting those errors but they slow things down and cause other problems. One way that digital quantum computers may get better is if new methods of error correction emerge. I am doubtful that something new will emerge, get fully tested, and then make it into production at scale all within the next ten years. So we may not see a quantum (ahem) leap in performance of quantum digital computers in the next decade.

Analog quantum computers are another matter. They are not switched, but instead are configured to directly simulate some physical system and the quantum evolution and interactions of components of that system. They are an embodied quantum model of that system. And they are ideally suited to solving these sorts of problems and cannot be emulated by conventional digital systems as they can be in the 39 bit number case above.

I find people working on quantum computers are often a little squirrelly about whether their computer acts more like a digital or analog computer, as they like to say they are “quantum” only. The winners over the next 10 years will be ones solving real problems in materials science and other aspects of chemistry and physics.

Self Driving Cars

In the US the players that will determine whether self driving cars are successful or abandoned are #1 Waymo (Google) and #2 Zoox (Amazon). No one else matters. The key metric will be human intervention rate as that will determine profitability.

Originally the term “self driving car” was about any sort of car that could operate without a driver on board, and without a remote driver offering control inputs. Originally they were envisioned as an option for privately owned vehicles used by individuals, a family car where no person needed to drive, but simply communicated to the car where it should take them.

That conception is no longer what people think of when self driving cars are mentioned. Self driving cars today refer to taxi-services that feel like Uber or Lyft, but for which there is not a human driver, just paying passengers.

In the US the companies that have led in this endeavor have changed over time.

The first leader was Cruise, owned by GM. They were the first to have a regular service in the downtown area of a major city (San Francisco), and then in a number of other cities, where there was an app that anyone could download and then use their service. They were not entirely forthcoming with operational and safety problems, including when they dragged a person, who had just been hit by a conventionally driven car, for tens of feet under one of their vehicles. GM suspended operations in late 2023 and completely disbanded it in December 2024.

Since then Waymo (owned by Google) has been the indisputable leading deployed service.

Zoox (owned by Amazon) has been a very distant, but operational, second place.

Tesla (owned by Tesla) has put on a facade of being operational, but it is not operational in the sense of the other two services, and faces regulatory headwinds that both Waymo and Zoox have long been able to satisfy. They are not on a path to becoming a real service.

See my traditional section on self driving cars below, as it explains in great detail the rationale for these evaluations. In short, Waymo looks to have a shot at succeeding and it is unlikely they will lose first place in this race. Zoox may also cross the finish line, and it is very unlikely that anyone will beat them. So if both of Waymo and Zoox fail, for whatever reason, the whole endeavor will grind to a halt in the US.

BUT…

But what might go wrong that makes one of these companies fail. We got a little insight into that in the last two weeks of 2025.

On Saturday December 20th of 2025 there was an extended power outage in San Francisco that started small in the late morning but by nightfall had spread to large swaths of the city. And lots and lots of normally busy intersections were by that time blocked by many stationary Waymos.

Traffic regulations in San Francisco are that when there is an intersection which has traffic lights that are all dark, that intersection should be treated as though it has stop signs at every entrance. Human drivers who don’t know the actual regulation tend to fall back to that behavior in any case.

It seemed that Waymos were waiting indefinitely for green lights that never came, and at intersections through which many Waymos were routed there were soon enough waiting Waymos that the intersections were blocked. Three days later, on December 23rd, Waymo issued an explanation on their blog site, which includes the following:

Navigating an event of this magnitude presented a unique challenge for autonomous technology. While the Waymo Driver is designed to handle dark traffic signals as four-way stops, it may occasionally request a confirmation check to ensure it makes the safest choice. While we successfully traversed more than 7,000 dark signals on Saturday, the outage created a concentrated spike in these requests. This created a backlog that, in some cases, led to response delays contributing to congestion on already-overwhelmed streets.

We established these confirmation protocols out of an abundance of caution during our early deployment, and we are now refining them to match our current scale. While this strategy was effective during smaller outages, we are now implementing fleet-wide updates that provide the Driver with specific power outage context, allowing it to navigate more decisively.

As the outage persisted and City officials urged residents to stay off the streets to prioritize first responders, we temporarily paused our service in the area. We directed our fleet to pull over and park appropriately so we could return vehicles to our depots in waves. This ensured we did not further add to the congestion or obstruct emergency vehicles during the peak of the recovery effort.

The key phrase is that Waymos “request a confirmation check” at dark signals. This means that the cars were asking for a human to look at images from their cameras and manually tell them how to behave. With 7,000 dark signals and perhaps a 1,000 vehicles on the road, Waymo clearly did not have enough humans on duty to handle the volume of requests that were coming in. Waymo does not disclose whether any human noticed a rise in these incidents early in the day and more human staff were called in, or whether they simply did not have enough employees to make handling them all possible.

At a deeper level it looks like they had a debugging feature in their code, and not enough people to supply real time support to handle the implications of that debugging feature. And it looks like Waymo is going to remove that debugging safety feature as a way of solving the problem. This is not an uncommon sort of engineering failure during early testing. Normally one would hope that the need for that debugging feature had been resolved before large scale deployment.

But, who are these human staff? Besides those in Waymo control centers, it turns out there is a gig-work operation with an app named Honk (the headline of the story is When robot taxis get stuck, a secret army of humans comes to the rescue) whereby Waymo pays people around $20 to do minor fixups to stuck Waymos by, for instance, going and physically closing a door that q customer left open. Tow truck operators use the same app to find Waymos that need towing because of some more serious problem. It is not clear whether it was a shortage of those gig workers, or a shortage of people in the Waymo remote operations center that caused the large scale failures. But it is worth noting that current generation Waymos need a lot of human help to operate as they do, from people in the remote operations center to intervene and provide human advice for when something goes wrong, to Honk gig-workers scampering around the city physically fixed problems with the vehicles, to people to clean the cars and plug them in to recharge when they return to their home base.

For human operated ride services, traditional taxi companies or gig services such as Uber and Lyft, do not need these external services. There is a human with the car at all times who takes care of these things.

The large scale failure on the 20th did get people riled up about these robots causing large scale traffic snarls, and made them wonder about whether the same thing will happen when the next big earthquake hits San Francisco. Will the human support worker strategy be stymied by both other infrastructure failures (e.g., the cellular network necessary for Honk workers to communicate) or the self preservation needs of the human workers themselves?

The Waymo blog post revealed another piece of strategy. This is one of three things they said that they would do to alleviate the problems:

Expanding our first responder engagement: To date, we’ve trained more than 25,000 first responders in the U.S. and around the world on how to interact with Waymo. As we discover learnings from this and other widespread events, we’ll continue updating our first responder training.

The idea is to add more responsibility to police and fire fighters to fix the inadequacies of the partial-only autonomy strategy for Waymo’s business model. Those same first responders will have more than enough on their plates during any natural disasters.

Will it become a political issue where the self-driving taxi companies are taxed enough to provide more first responders? Will those costs ruin their business model? Will residents just get so angry that they take political action to shut down such ride services?

Humanoid Robots

Deployable dexterity will remain pathetic compared to human hands beyond 2036. Without new types of mechanical systems walking humanoids will remain too unsafe to be in close proximity to real humans.

Despite this prediction it is worth noting that there is a long distance between current deployed dexterity and dexterity that is still pathetic. In the next ten years deployable dexterity may improve markedly, but not in the way the current hype for humanoid robots suggests. I talk about his below in my annual section scoring my 2018 predictions on robotics, AI, and machine learning, in a section titled Dexterous Hands.

Towards the end of 2025 I published a long blog post summarizing the status of, and problems remaining for humanoid robots.

I started building humanoid robots in my research group at MIT in 1992. My previous company, Rethink Robotics, founded in 2008, delivered thousands of upper body Baxter and Sawyer humanoid robots (built in the US) to factories between 2012 and 2018. At the top of this blog page you can see a whole row of Baxter robots in China. A Sawyer robot that had operated in a factory in Oregon just got shut down in late 2025 with 35,236 hours on its operations clock. You can still find many of Rethink’s humanoids in use in teaching and research labs around the world. Here is the cover of Science Robotics from November 2025,

showing a Sawyer used in the research for this article out of Imperial College, London.

Here is a slide from a 1998 powerpoint deck that I was using in my talks, six years after my graduate students and I had started building our first humanoid robot, Cog.

It is pretty much the sales pitch that today’s humanoid companies use. You are seeing here my version from almost twenty eight years ago.

I point this out to demonstrate that I am not at all new to humanoid robotics and have worked on them for decades in both academia and in producing and selling humanoid robots that were deployed at scale (which no one else has done) doing real work.

My blog post from September, details why the current learning based approaches to getting dexterous manipulation will not get there anytime soon. I argue that the players are (a) collecting the wrong data and (b) trying to learn the wrong thing. I also give an argument (c) for why learning might not be the right approach. My argument for (c) may not hold up, but I am confident that I am right on both (a) and (b), at least for the next ten years.

I also outline in that blog post why the current (and indeed pretty much the only, for the last forty years) method of building bipeds and controlling them will remain unsafe for humans to be nearby. I pointed out that the danger is roughly cubicly proportional to the weight of the robot. Many humanoid robot manufacturers are introducing lightweight robots, so I think they have come to the same conclusion. But the side effect is that the robots can not carry much payload, and certainly can’t provide physical support to elderly humans, which is a thing that human carers do constantly — these small robots are just not strong enough. And elder care and in home care is one of the main arguments for having human shaped robots, adapted to the messy living environments of actual humans.

Given that careful analysis from September I do not share the hype that surrounds humanoid robotics today. Some of it is downright delusional across many different levels.

To believe the promises of many CEOs of humanoid companies you have to accept the following conjunction.

- Their robots have not demonstrated any practical work (I don’t count dancing in a static environment doing exactly the same set of moves each time as practical work).

- The demonstrated grasping, usually just a pinch grasp, in the videos they show is at a rate which is painfully slow and not something that will be useful in practice.

- They claim that their robots will learn human-like dexterity but they have not shown any videos of multi-fingered dexterity where humans can and do grasp things that are unseen, and grasp and simultaneously manipulate multiple small objects with one hand. And no demonstrations of using the body with the hands which is how humans routinely carry many small things or one or two heavy things.

- They show videos of non tele-operated manipulation, but all in person demonstrations of manipulation are tele-operated.

- Their current plans for robots working in customer homes all involve a remote person tele-operating the robot.

- Their robots are currently unsafe for humans to be close to when they are walking.

- Their robots have no recovery from falling and need human intervention to get back up.

- Their robots have a battery life measured in minutes rather than hours.

- Their robots cannot currently recharge themselves.

- Unlike human carers for the elderly, humanoids are not able to provide any physical assistance to people that provides stabilizing support for the person walking, getting into and out of bed physical assistance, getting on to and off of a toilet, physical assistance, or indeed any touch based assistance at all.

- The CEOs claim that there robots will be able to do everything, or many things, or a lot of things, that a human can do in just a few short years. They currently do none.

- The CEOs claim a rate of adoption of these humanoid robots into homes and industries at a rate that is multiple orders of magnitude faster than any other technology in human history, including mainframe computers, and home computers and the mobile phones, and the internet. Many orders of magnitude faster. Here is a CEO of a humanoid robot company saying that they will be in 10% of US households by 2030. Absolutely no technology (even without the problems above) has ever come close to scaling at that rate.

The declarations being made about humanoid robots are just not plausible.

We’ll see what actually happens over the next ten years, but it does seem that the fever is starting to crack at the edges. Here are two news stories from the last few days of 2025.

From The Information on December 22nd there is a story about how humanoid robot companies are wrestling with safety standards. All industrial and warehouse robots, whether stationary of mobile have a big red safety stop button, in order to comply with regulatory safety standards. The button cuts the power to the motors. But cutting power to the motors of a balancing robot might make them fall over and cause more danger and damage to people nearby. For the upper torso humanoid robots Baxter and Sawyer from my company Rethink Robotics we too had a safety stop button that cut power to all the motors in the arms. It was a collaborative robot and often a person, or part of their limbs or body could be under an arm and it would have been dangerous for the arms to fall quickly on cutoff of power. To counter this we developed a unique circuit that required no active power, which made it so that the back current generated by a motor when powered off acted as a very strong brake. Perhaps there are similar possible solutions for humanoid robots and falling, but they need to be invented yet.

On December 25th the Wall Street Journal had a story headlined “Even the Companies Making Humanoid Robots Think They’re Overhyped”, with a lede of “Despite billions in investment, startups say their androids mostly aren’t useful for industrial or domestic work yet”. Here are the first two paragraphs of the story:

Billions of dollars are flowing into humanoid robot startups, as investors bet that the industry will soon put humanlike machines in warehouses, factories and our living rooms.

Many leaders of those companies would like to temper those expectations. For all the recent advances in the field, humanoid robots, they say, have been overhyped and face daunting technical challenges before they move from science experiments to a replacement for human workers.

And then they go on to quote various company leaders:

“We’ve been trying to figure out how do we not just make a humanoid robot, but also make a humanoid robot that does useful work,” said Pras Velagapudi, chief technology officer at Agility Robotics.

Then talking about a recent humanoid robotics industry event the story says:

On stage at the summit, one startup founder after another sought to tamp down the hype around humanoid robots.

“There’s a lot of great technological work happening, a lot of great talent working on these, but they are not yet well defined products,” said Kaan Dogrusoz, a former Apple engineer and CEO of Weave Robotics.

Today’s humanoid robots are the right idea, but the technology isn’t up to the premise, Dogrusoz said. He compared it to Apple’s most infamous product failure, the Newton hand-held computer.

There are more quotes from other company leaders all pointing out the difficulties in making real products that do useful work. Reality seems to be setting in as promised delivery dates come and go by.

Meanwhile here is what I said at the end of my September blog post about humanoid robots and teaching them dexterity. I am not at all negative about a great future for robots, and in the nearish term. It is just that I completely disagree with the hype arguing that building robots with humanoid form magically will make robots useful and deployable. These particular paragraphs followed where I had described there, as I do again in this blog post, how the meaning of self driving cars has drifted over time.

Following that pattern, what it means to be a humanoid robot will change over time.

Before too long (and we already start to see this) humanoid robots will get wheels for feet, at first two, and later maybe more, with nothing that any longer really resembles human legs in gross form. But they will still be called humanoid robots.

Then there will be versions which variously have one, two, and three arms. Some of those arms will have five fingered hands, but a lot will have two fingered parallel jaw grippers. Some may have suction cups. But they will still be called humanoid robots.

Then there will be versions which have a lot of sensors that are not passive cameras, and so they will have eyes that see with active light, or in non-human frequency ranges, and they may have eyes in their hands, and even eyes looking down from near their crotch to see the ground so that they can locomote better over uneven surfaces. But they will still be called humanoid robots.

There will be many, many robots with different forms for different specialized jobs that humans can do. But they will all still be called humanoid robots.

As with self driving cars, most of the early players in humanoid robots, will quietly shut up shop and disappear. Those that remain will pivot and redefine what they are doing, without renaming it, to something more achievable and with, finally, plausible business cases. The world will slowly shift, but never fast enough to need a change of name from humanoid robots. But make no mistake, the successful humanoid robots of tomorrow will be very different from those being hyped today.

Neural Computation

There will be small and impactful academic forays into neuralish systems that are well beyond the linear threshold systems, developed by 1960, that are the foundation of recent successes. Clear winners will not yet emerge by 2036 but there will be multiple candidates.

Current machine learning techniques are largely based on having millions, and more recently tens (to hundreds?) of billions, of linear threshold units. They look like this.

Each of these units have a fixed number of inputs, where some numerical value comes in, and it is multiplied by a weight, usually a floating point number, and the results of all of the multiplications are summed, along with an adjustable threshold ![]() , which is usually negative, and then the sum goes through some sort of squishing function to produce a number between zero and one, or in this case minus one and plus one, as the output. In this diagram, which, by the way is taken from Bernie Widrow’s technical report from 1960, the output value is either minus one or plus one, but in modern systems it is often a number from anywhere in that, or another, continuous interval.

, which is usually negative, and then the sum goes through some sort of squishing function to produce a number between zero and one, or in this case minus one and plus one, as the output. In this diagram, which, by the way is taken from Bernie Widrow’s technical report from 1960, the output value is either minus one or plus one, but in modern systems it is often a number from anywhere in that, or another, continuous interval.

This was based on previous work, including that of Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts’ 1943 formal model of a neuron, Marvin Minsky’s 1954 Ph.D. dissertation on using reinforcement for learning in a machine based on model neurons, and Frank Rosenblatt’s 1957 use of weights (see page 10) in an analog implementation of a neural model.

These are what current learning mechanisms have at their core. These! A model of biological neurons that was developed in a brief moment of time from 83 to 65 years ago. We use these today. They are extraordinarily primitive models of neurons compared to what neuroscience has learned in the subsequent sixty five years.

Since the 1960s higher levels of organization have been wrapped around these units. In 1979 Kunihiko Fukushima published (at the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI 1979, Tokyo — coincidentally the first place where I published in an international venue) his first English language description of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which allowed for position invariant recognition of shapes (in his case, hand written digits), without having to learn about those shapes in every position within images.

Then came backpropagation, a method where a network can be told the correct output it should have produced, and by propagating the error backwards through the derivative of the quantizer in the diagram above (note that the quantizer shown there is not differentiable–a continuous differentiable quantizer function is needed to make the algorithm work), a network can be trained on examples of what it should produce. The details of this algorithm, are rooted in the chain rule of Gottfried Leibniz in 1676 through a series of modern workers from around 1970 through about 1982. Frank Rosenblatt (see above) had talked about a “back-propagating error correction” in 1962, but did not know how to implement it.

In any case, the linear threshold neurons, CNNs, and backpropagation are the basis of modern neural networks. After an additional 30 years of slow but steady progress they burst upon the scene as deep learning, and unexpectedly crushed many other approaches to computer vision — the research field of getting computers to interpret the contents of an image. Note that “deep” learning refers to there being lots of layers (around 12 layers in 2012) of linear threshold neurons rather than the smaller number of layers (typically two or three) that had been used previously.

Now LLMs are built on top of these sorts of networks with many more layers, and many subnetworks. This is what got everyone excited about Artificial Intelligence, after 65 years of constant development of the field.

Despite their successes with language, LLMs come with some serious problems of a purely implementation nature.

First, the amount of examples that need to be shown to a network to learn to be facile in language takes up enormous amounts of computation, so the that costs of training new versions of such networks is now measured in the billions of dollars, consuming an amount of electrical power that requires major new investments in electrical generation, and the building of massive data centers full of millions of the most expensive CPU/GPU chips available.

Second, the number of adjustable weights shown in the figure are counted in the hundreds of billions meaning they occupy over a terabyte of storage. RAM that is that big is incredibly expensive, so the models can not be used on phones or even lower cost embedded chips in edge devices, such as point of sale terminals or robots.

These two drawbacks mean there is an incredible financial incentive to invent replacements for each of (1) our humble single neuron models that are close to seventy years old, (2) the way they are organized into networks, and (3) the learning methods that are used.

That is why I predict that there will be lots of explorations of new methods to replace our current neural computing mechanisms. They have already started and next year I will summarize some of them. The economic argument for them is compelling. How long they will take to move from initial laboratory explorations to viable scalable solutions is much longer than everyone assumes. My prediction is there will be lots of interesting demonstrations but that ten years is too small a time period for a clear winner to emerge. And it will take much much longer for the current approaches to be displaced. But plenty of researchers will be hungry to do so.

LLMs

LLMs that can explain which data led to what outputs will be key to non annoying/dangerous/stupid deployments. They will be surrounded by lots of mechanism to keep them boxed in, and those mechanisms, not yet invented for most applications, will be where the arms races occur.

The one thing we have all learned, or should have learned, is that the underlying mechanism for Large Language Models does not answer questions directly. Instead, it gives something that sounds like an answer to the question. That is very different from saying something that is accurate. What they have learned is not facts about the world but instead a probability distribution of what word is most likely to come next given the question and the words so far produced in response. Thus the results of using them, uncaged, is lots and lots of confabulations that sound like real things, whether they are or not.

We have seen all sorts of stories about lawyers using LLMs to write their briefs, judges using them to write their opinions, where the LLMs have simply made up precedents and fake citations (that sound plausible) for those precedents.

And there are lesser offenses that are still annoying but time consuming. The first time I used ChatGPT was when I was retargeting the backend of a dynamic compiler that I had used on half a dozen architectures and operating systems over a thirty year period, and wanted to move it to the then new Apple M1 chips. The old methods of changing a chunk of freshly compiled binary from data as it was spit out by the compiler, into executable program, no longer worked, deliberately so as part of Apple’s improved security measures. ChatGPT gave me detailed instructions on what library calls to use, what their arguments were, etc. The names looked completely consistent with other calls I knew within the Apple OS interfaces. When I tried to use them from C, the C linker complained they didn’t exist. And then when I asked ChatGPT to show me the documentation it groveled that indeed they did not exist and apologized.

So we all know we need guard rails around LLMs to make them useful, and that is where there will be lot of action over the next ten years. They can not be simply released into the wild as they come straight from training.

This is where the real action is now. More training doesn’t make things better necessarily. Boxing things in does.

Already we see companies trying to add explainability to what LLMs say. Google’s Gemini now gives real citations with links, so that human users can oversee what they are being fed. Likewise, many companies are trying to box in what their LLMs can say and do. Those that can control their LLMs will be able to deliver useable product.

A great example of this is the rapid evolution of coding assistants over the last year or so. These are specialized LLMs that do not give the same sort of grief to coders that I experienced when I first tried to use generic ChatGPT to help me. Peter Norvig, former chief scientist of Google, has recently produced a great report on his explorations of the new offerings. Real progress has been made in this high impact, but narrow use field.

New companies will become specialists in providing this sort of boxing in and control of LLMs. I had seen an ad on a Muni bus in San Francisco for one such company, but it was too fleeting to get a photo. Then I stumbled upon this tweet that has three such photos of different ads from the same company, and here is one of them:

The four slogans on the three buses in the tweet are: Get your AI to behave, When your AI goes off leash, Get your AI to work, and Evaluate, monitor, and guardrail your AI. And “the AI” is depicted as a little devil of sorts that needs to be made to behave.

Self Driving Cars

This is one of my three traditional sections where I update one of my three initial tables of prediction from my predictions exactly eight years ago today. In this section I talk about self driving cars, driverless taxi services, and what that means, my own use of driverless taxi services in the previous year, adoption of electric vehicles in the US, and flying cars and taxis, and what those terms mean.

No entries in the table specifically involve 2025 or 2026, and the status of predictions that are further out in time remain the same. I have only put in one new comment, about how many cities in the US will have self-driving (sort of) taxi services in 2026 and that comment is highlighted,

| Prediction [Self Driving Cars] | Date | 2018 Comments | Updates |

|---|---|---|---|

| A flying car can be purchased by any US resident if they have enough money. | NET 2036 | There is a real possibility that this will not happen at all by 2050. | |

| Flying cars reach 0.01% of US total cars. | NET 2042 | That would be about 26,000 flying cars given today's total. | |

| Flying cars reach 0.1% of US total cars. | NIML | ||

| First dedicated lane where only cars in truly driverless mode are allowed on a public freeway. | NET 2021 | This is a bit like current day HOV lanes. My bet is the left most lane on 101 between SF and Silicon Valley (currently largely the domain of speeding Teslas in any case). People will have to have their hands on the wheel until the car is in the dedicated lane. | |

| Such a dedicated lane where the cars communicate and drive with reduced spacing at higher speed than people are allowed to drive | NET 2024 | 20240101 This didn't happen in 2023 so I can call it now. But there are no plans anywhere for infrastructure to communicate with cars, though some startups are finally starting to look at this idea--it was investigated and prototyped by academia 20 years ago. |

|

| First driverless "taxi" service in a major US city, with dedicated pick up and drop off points, and restrictions on weather and time of day. | NET 2021 | The pick up and drop off points will not be parking spots, but like bus stops they will be marked and restricted for that purpose only. | 20240101 People may think this happened in San Francisco in 2023, but it didn't. Cruise has now admitted that there were humans in the loop intervening a few percent of the time. THIS IS NOT DRIVERLESS. Without a clear statement from Waymo to the contrary, one must assume the same for them. Smoke and mirrors. |

| Such "taxi" services where the cars are also used with drivers at other times and with extended geography, in 10 major US cities | NET 2025 | A key predictor here is when the sensors get cheap enough that using the car with a driver and not using those sensors still makes economic sense. | 20250101 Imminent dual use of personal cars was the carrot that got lots of people to pay cash when buying a Tesla for the software subscription that would allow their car to operate in this way. Shockingly the CEO of Tesla announced in smoke and mirrors roll out of Cyber Cab in 2024, that the service would use specially built vehicles to be produced at some indeterminate late date. I got suckered by his hype. This is unlikely to happen in the first half of this century. |

| Such "taxi" service as above in 50 of the 100 biggest US cities. | NET 2028 | It will be a very slow start and roll out. The designated pick up and drop off points may be used by multiple vendors, with communication between them in order to schedule cars in and out. | 20250101 Even the watered down version of this with remote operators is not gong to happen in 50 cities by 2028. Waymo has it in 3 cities and is currently planning on 2 more in the US in 2025. 20260101 Waymo did indeed add two cities in 2025, Austin and Atlanta. In those two cities they use Uber as their booking service. They are also expanding the metropolitan reach in their existing cities San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Phoenix. They have promised five more US cities in 2026, i.e., they promise to double the number of cities this year. They would have to then quintuple in 2027 to beat my prediction. Unlikely. |

| Dedicated driverless package delivery vehicles in very restricted geographies of a major US city. | NET 2023 | The geographies will have to be where the roads are wide enough for other drivers to get around stopped vehicles. | |

| A (profitable) parking garage where certain brands of cars can be left and picked up at the entrance and they will go park themselves in a human free environment. | NET 2023 | The economic incentive is much higher parking density, and it will require communication between the cars and the garage infrastructure. | |

| A driverless "taxi" service in a major US city with arbitrary pick and drop off locations, even in a restricted geographical area. | NET 2032 NET 2032 | This is what Uber, Lyft, and conventional taxi services can do today. | 20240101 Looked like it was getting close until the dirty laundry came out. 20250101 Waymo now has a service that looks and feels like this in San Francisco, 8 years earlier than I predicted. But it is not what every one was expecting. There are humans in the loop. And for those of us who use it regularly we know it is not as general case on drop off and pick up as it is with human drivers. |

| Driverless taxi services operating on all streets in Cambridgeport, MA, and Greenwich Village, NY. | NET 2035 | Unless parking and human drivers are banned from those areas before then. | |

| A major city bans parking and cars with drivers from a non-trivial portion of a city so that driverless cars have free reign in that area. | NET 2027 BY 2031 | This will be the starting point for a turning of the tide towards driverless cars. | |

| The majority of US cities have the majority of their downtown under such rules. | NET 2045 | ||

| Electric cars hit 30% of US car sales. | NET 2027 | 20240101 This one looked pessimistic last year, but now looks at risk. There was a considerable slow down in the second derivative of adoption this year in the US. 20250101 Q3 2024 had the rate 8.9% so there is no way it can reach 30% in 2027. I was way too optimistic at a time when EV enthusiasts thought I was horribly pessimistic. |

|

| Electric car sales in the US make up essentially 100% of the sales. | NET 2038 | ||

| Individually owned cars can go underground onto a pallet and be whisked underground to another location in a city at more than 100mph. | NIML | There might be some small demonstration projects, but they will be just that, not real, viable mass market services. | |

| First time that a car equipped with some version of a solution for the trolley problem is involved in an accident where it is practically invoked. | NIML | Recall that a variation of this was a key plot aspect in the movie "I, Robot", where a robot had rescued the Will Smith character after a car accident at the expense of letting a young girl die. |

A Brief Recap of what “Self Driving” Cars Means and Meant

This is a much abridged and updated version of what I wrote exactly one year ago today.

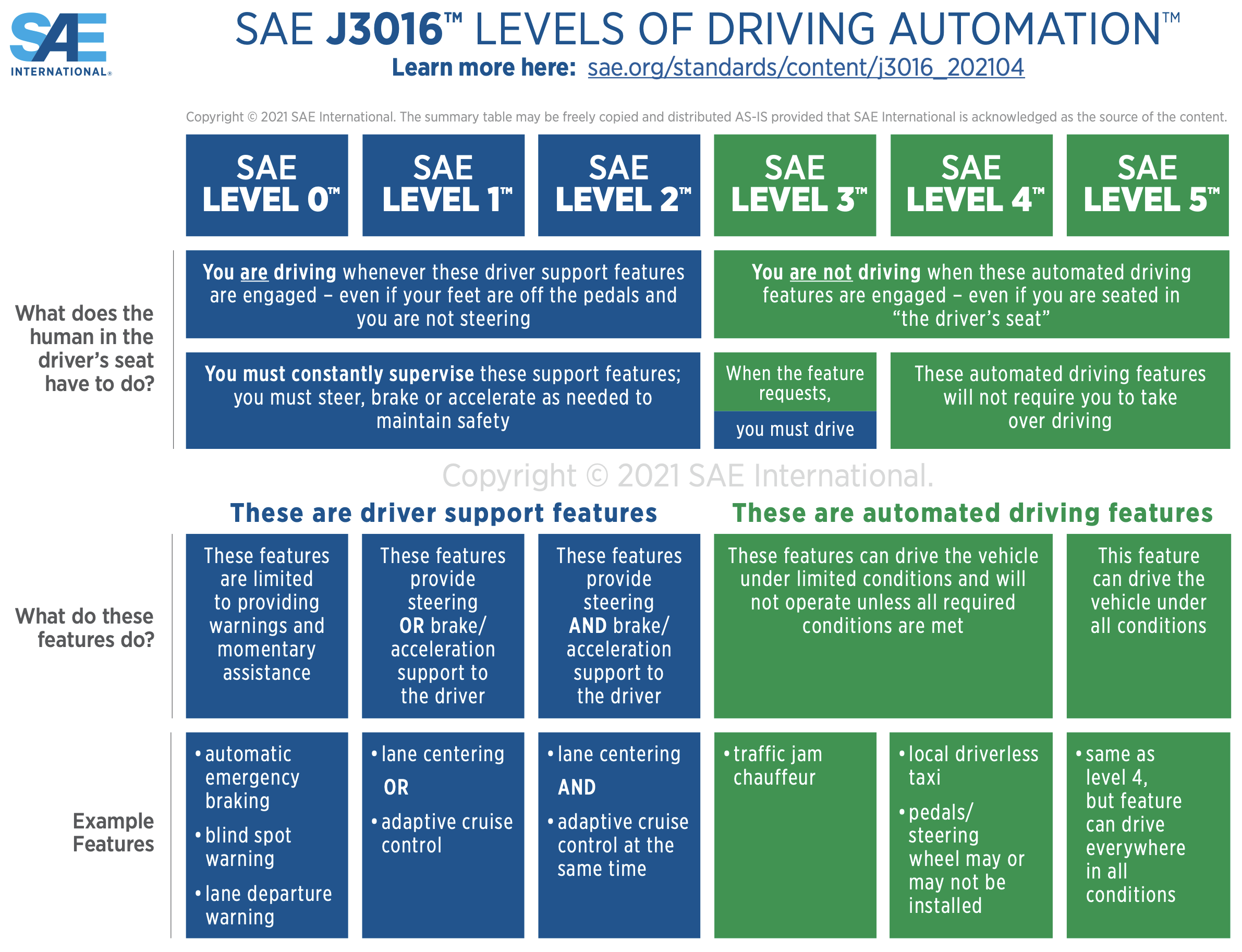

The definition, or common understanding, of what self driving cars really means has changed since my post on predictions eight years ago. At that time self driving cars meant that the cars would drive themselves to wherever they were told to go with no further human control inputs. It was implicit that it meant level 4 driving. Note that there is also a higher level of autonomy, level 5, that is defined.

Note that in the second row of content, it says that there will be no need for a human to take over for either level 4 or level 5. For level 4 there may be pre-conditions on weather and within a supported geographic area. Level 5 eliminates pre-conditions and geographic constraints. So far no one is claiming to have level 5.

However the robot taxi services such as Cruise (now defunct), Waymo, currently operating in five US cities, and Zoox, currently operating in two cities with limited service (Las Vegas and San Francisco), all relied, or rely, on having remote humans who the car can call on to help get them out of situations they cannot handle. That is not what level 4 promises. To an outside observer it looks like level 4, but it is somewhat less than that in reality. This is not the same as a driver putting their hands back on the steering wheel in real time, but it does mean that there is sometimes a remote human giving high level commands to the car. The companies do not advertise how often this happens, but it is believed to be every few miles of driving. The Tesla self driving taxis in Austin have a human in the passenger seat to intervene when there is a safety concern.

One of the motivations for self driving cars was that the economics of taxis, cars that people hire at any time for a short ride of a few miles from where they are to somewhere else of their choosing, would be radically different as there would be no driver. Systems which do require remote operations assistance to get full reliability cut into that economic advantage and have a higher burden on their ROI calculations to make a business case for their adoption and therefore their time horizon to scaling across geographies.

Actual self-driving is now generally accepted to be much harder than every one believed.

As a reminder of how strong the hype was and the certainty of promises that it was just around the corner here is a snapshot of a whole bunch of predictions by major executives from 2017.

I have shown this many times before but there are three new annotations here for 2025 in the lines marked by a little red car. The years in parentheses are when the predictions were made. The years in blue are the predicted years of achievement. When a blue year is shaded pink it means that it did not come to pass by then. The predictions with orange arrows are those that I had noticed had later been retracted.

It is important to note that every prediction that said something would happen by a year up to and including 2025 did not come to pass by that year. In fact none of those have even come to pass by today. NONE. Eighteen of the twenty predictions were about things that were supposed to have happened by now, some as long as seven years ago. NONE of them have happened yet.

My Own Experiences with Waymo in 2025

I took two dozen rides with Waymo in San Francisco this year. There is still a longer wait than for an Uber at most times, at least for where I want to go. My continued gripe with Waymo is that it selects where to pick me up, and it rarely drops me right at my house — but without any indication of when it is going to choose some other drop off location for me.

The other interaction I had was in early November when I felt like I was playing bull fighter, on foot, to a Waymo vehicle. My house is on a very steep hill in San Francisco, with parallel parking on one side and ninety degree parking on the other side. It is rare that two cars can pass each other traveling in opposite directions without one having to pull over into some empty space somewhere.

In this incident I was having a multi-hundred pound pallet of material deliverd to my home. There was a very big Fedex truck parked right in front of my house, facing uphill, and the driver/operator was using a manual pallet jack to get it onto the back lift gate, but the load was nine feet long so it hung out past the boundary of the truck. An unoccupied Waymo came down the hill and was about to try to squeeze past the truck on that side. Perhaps it would have made it through if there was no hanging load. So I ran up to just above the truck on the slope and tried to get the Waymo to back up by walking straight at it. Eventually it backed up and pulled in a little bit and sat still. Within a minute it tried again. I pushed it back with my presence again. Then a third time. Let’s be clear it would have been a dangerous situation if it had done what it was trying to do and could have injured the Fedex driver who it had not seen at all. But any human driver would have figured out what was going on and that the Fedex truck would never go down the hill backwards but would eventually drive up the hill. Any human driver would have replanned and turned around. After the third encounter the Waymo stayed still for a while. Then it came to life and turned towards the upwards direction, and when it was at about a 45 degree angle to the upward line of travel it stopped for a few seconds. Then it started again and headed up and away. I infer that eventually the car had called for human help, and when the human got to it, they directed it where on the road to go to (probably with a mouse click interface) and once it got there it paused and replanned and then headed in the appropriate direction that the human had made it already face.

Self Driving Taxi Services

There have been three self driving taxi services in the US in various stages of play over the last handful of years, though it turns out, as pointed out above that all of them have remote operators. They are Waymo, Cruise, and Zoox.

___Cruise

Cruise died in both 2023 and 2024, and is now dead, deceased, an ex self driving taxi service. Gone. I see its old cars driving around the SF Bay Area, with their orange paint removed, and with humans in the driver seat. On the left below are two photos I took on May 30th at a recharge station. “Birdie” looked just like an old Cruise self driving taxi, but without an orange paint. I hunted around around in online stories about Cruise and soon found another “Birdie”, with orange paint, and the same license plate. So GM are using them to gather data, perhaps for training their level 3 driving systems.

___Tesla

Tesla announced to much hoopla that they were starting a self driving taxi service this year, in Austin. It requires a safety person to be sitting in the front passenger seat at all times. Under the certification with which they operate, on occasion that front seat person is required to move to the driver’s seat. Then it just becomes a regular Tesla with a person driving it and FSD enabled. The original fleet was just 30 vehicles, with at least seven accidents reported by Tesla by October, even with the front seat Tesla person. In October the CEO announced that the service would expand to 500 vehicles in Austin in 2025. By November he had changed to saying they would double the fleet. That makes 60 vehicles. I have no information that it actually happened.

He also said he wanted to expand the “Robotaxi” service to Phoenix, San Francisco, Miami, Las Vegas, Dallas, and Houston by the end of 2025. It appears that Tesla can not get permits to run even supervised (mirroring the Austin deployment) in any of those cities. And no, they are not operating in any of those cities and now 2025 has reached its end.

In mid-December there were confusing reports saying that Tesla now had Model Y’s driving in Austin without a human safety monitor on board but that the Robotaxi service for paying customers (who are still people vetted by Tesla) resumed their human safety monitors. So that is about three or four years behind Waymo in San Francisco, and not at all at scale.

The CEO of Tesla has also announced (there are lots of announcements and they are often very inconsistent…) that actually the self driving taxis will be a new model with no steering wheel nor other driver controls. So they are years away from any realistic deployment. I will not be surprised if it never happens as the lure of humanoids completely distracts the CEO. If driving with three controls, (1) steering angle of the front wheels, (2) engine torque (on a plus minus continuum), and (3) brake pedal pressure, are too hard to make actually work safely for real, how hard can it be to have a program control a heavy unstable balancing platform with around 80 joints in hips and waist, two legs, two arms and five articulated fingers on each hand?

___Waymo

Meanwhile Waymo had raised $5.6B to expand to new cities in 2025. It already operated in parts of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Phoenix. During 2025 it expanded to Austin and Atlanta, the cities it had promised. It also increased its geographic reach in its existing cities and surrounding metropolitan areas. In the original three cities users have a Waymo app on their phone and specifically summon a Waymo. In the new cities however they used a slightly different playbook. In both Austin and Atlanta people use their standard Uber app. They can update their preference to say that they prefer to get a Waymo rather than a human driven car, but there is no guarantee that a Waymo is what they will get. And any regular user of the Uber app in those cities may be offered a Waymo, but they do get an option to decline and to continue to wait for a human driven offer.

In the San Francisco area, beyond the city itself, Waymo first expanded by operating in Palo Alto, in a geographically separate area. Throughout the year one could see human operated Waymos driving in locations all along the peninsula from San Francisco to Palo Alto and further south to San Jose. By November Waymo had announced driverless operations throughout that complete corridor, an area of 260 square miles, but not quite yet on the freeways–the Waymos are operating on specific stretches of both 101 and 280, but only for customers who have specifically signed up for that possibility. Waymo is now also promising to operate at the two airports, San Jose and San Francisco. The San Jose airport came first, and San Francisco airport is operating in an experimental mode with a human in the front seat.

Waymo has announced that it will expand to five more cities in the US during 2026; Miami, Dallas, Houston, San Antonio, and Orlando. It seems likely, given their step by step process, and their track record of meeting their promises that Waymo has a good shot at getting operations running in these five cities, doubling their total number of US cities to 10.

Note that although it does very occasionally snow in five of these ten cities (Atlanta, Austin, Houston, San Antonio, and Orlando) it is usually only a dusting. It is not yet clear whether Waymo will operate when it does snow. It does not snow in the other five cities, and in San Francisco Waymo is building to be a critical part of the transportation infrastructure. How well that would work if a self driving taxi service was subject to tighter restrictions than human driven services due to weather could turn into a logistical nightmare for the cities themselves. In the early days of Cruise they did shut down whenever there was a hint of fog in San Francisco, and that is a common occurrence. It was annoying for me, but Cruise never reached the footprint size in San Francisco that Waymo now enjoys.

No promises yet from Waymo about when it might start operating in cities that do commonly have significant snow accumulations.

In May of 2025 Waymo announced a bunch of things in one press release. First, that they had 1,500 Jaguar-based vehicles at that time, operating in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Austin. Second, that they were no longer taking deliveries of any more Jaguars from Jaguar, but that they were now building two thousand of their own Jaguars in conjunction with Magna (a tier one auto supplier that also builds small run models of big brands — e.g., they build all the Mini Coopers that BMW sells) in Mesa, Arizona. Third, that they would also start building, in late 2025, versions of the Zeekr RT, a vehicle that they co-designed with Chinese company Geely, that can be built with no steering wheel or other controls for humans, but with sensor systems that are self-cleaning.

It is hard to track exactly how many Waymos are deployed, but in August 2025, this website, citing various public disclosures by Waymo, put together the following estimates for the five cities in which Waymo was operating.

Phoenix 400 San Francisco 800 Los Angeles 500 Austin 100 Atlanta 36

No doubt those numbers have increased by now. Meanwhile Waymo has annualized revenues of about $350M and is considering an IPO with a valuation of around $100B. With numbers like those it can probably raise significant growth capital independently from its parent company.

___Zoox

The other self driving taxi system deployed in the US is Zoox which is currently operating only in small geographical locations within Las Vegas and San Francisco. Their deployment vehicles have no steering wheel or other driver controls–they have been in production for many years. I do notice, by direct observation as I drive and walk around San Francisco, that Zoox has recently enlarged the geographic areas where its driverful vehicles operate, collecting data across all neighborhoods. So far the rides are free on Zoox, but only for people who have gone through an application process with the company. Zoox is following a pattern established by both Cruise and Waymo. It is roughly four years behind Cruise and two years behind Waymo, though it is not clear that it has the capital available to scale as quickly as either of them.

All three companies that have deployed actual uncrewed self driving taxi services in the US have been partially or fully owned by large corporations. GM owned Cruise, Waymo is partially spun out of Google/Alphabet, and Zoox is owned by Amazon.

Cruise failed. If any other company wants to compete with Waymo or Zoox, even in cities where they do not operate, it is going to need a lot of capital. Waymo and Zoox are out in front. If one or both of them fail, or lose traction and fail to grow, and grow very fast, it will be near to impossible for other companies to raise the necessary capital.

So it is up to Waymo and Zoox. Otherwise, no matter how well the technology works, the dream of driverless taxis is going to be shelved for many years.

Electric Cars

In my original predictions I said that electric car (and I meant battery electric, not hybrids) sales would reach 30% of the US total no earlier than 2027. A bunch of people on twitter claimed I was a pessimist. Now it looks like I was an extreme optimist as it is going to take a real growth spurt to reach even 10% in 2026, i.e., earlier than 2027.

Here is the report that I use to track EV sales — it is updated every few weeks. In this table I have collected the quarterly numbers that are finalized. The bottom row is the percentage of new car sales that were battery electric.

| '22 | '22 | '22 | '22 | '23 | '23 | '23 | '23 | '24 | '24 | '24 | '24 | '25 | '25 | '25 |

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 |

| 5.3 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.9 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 10.5 |

Although late in 2024 EV sales were pushing up into the high eight percentage points they have dropped back into the sevens this year in the first half of the year. Then they picked up to 10.5% in the third quarter of 2025, but that jump was expected as the Federal electric vehicle (EV) tax credits ended for all new and used vehicles purchased after September 30, 2025, as part of the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act”. People bought earlier than they might have in order to get that tax credit, so the industry is expecting quite a slump in the fourth quarter, but it will be a couple more months before the sales figures are all in. YTD 2025 is still under 8.5%, and is likely to end at under 8%.

The trends just do not look like we will get to EVs reaching 12% of US cars being sold in 2027, even with a huge uptick. 30% is just not going to happen.

As for which brands are doing better than others, Tesla’s sales dropped a lot more than the rest of the market. Brand winners were GM, Hyundai, and Volkswagen.

The US experience is not necessarily the experience across the world. For instance Norway reached 89% fully electric vehicles of all sold in 2024, largely due to taxes on gasoline powered car purchases. But that is a social choice of the people of Norway, not at all driven by oil availability. With a population of 5.6 million compared to the US with 348 million, and domestic oil production of 2.1 million barrels per day, compared to the US with 13.4 million b/d, Norway has a per capita advantage of almost ten times as much oil per person (9.7 to be more precise).

Electrification levels of cars is a choice that a country makes.

Flying Cars

The next two paragraphs are reproduced from last’s years scorecard.

Flying cars are another category where the definitions have changed. Back when I made my predictions it meant a vehicle that could both drive on roads and fly through the air. Now it has come to mean an electric multi-rotor helicopter than can operate like a taxi between various fixed landing locations. Often touted are versions that have no human pilot. These are known as eVTOLs, for “electric vertical take off & landing”.

Large valuations have been given to start ups who make nice videos of their electric air taxis flying about. But on inspection one sees that they don’t have people in them. Often, you might notice, even those flights are completely over water rather than land. I wrote about the lack of videos of viable prototypes back in November 2022.

The 2022 post referred to in the last sentence was trying to make sense of a story about a German company, Volocoptor, receiving a $352M Series E investment. The report from pitchbook predicted world wide $1.5B in revenue in the eVTOL taxi service market for 2025. I was bewildered as I could not find a single video, as of the end of 2022, of a demo of an actual flight profile with actual people in an actual eVTOL of the sort of flights that the story claimed would be generating that revenue in just 3 years.

I still can’t find such a video. And the actual revenue for actual flights in 2025 turned out to be $0.0B (and there are no rounding errors there — it was $0) and Volocoptor has gone into receivership, with a “reorganization success” in March 2025.

In my November 2022 blog post above I talked about another company, Lilium, which came the closest to having a video of a real flight, but it was far short of carrying people and it did not fly as high as is needed for air taxi service. At the time Lilium had 800 employees. Since then Lilium has declared bankruptcy not once (December 2024), but twice (February 2025), after the employees had been working for some time without pay.

But do not fear. There are other companies on the very edge of succeeding. Oh, and an edge means that sometimes you might fall off of it.

Here is an interesting report on the two leading US eVTOL companies, Archer and Joby Aviation, both aiming at the uncrewed taxi service market; both with valuations in the billions, and both missing just one thing. A for real live working prototype.

The story focuses on a pivotal point, the moment when an eVTOL craft has risen vertically, and now needs to transition to forward motion. In particular it points out that Archer has never demonstrated that transition, even with a pilot onboard, and during 2025 they cancelled three scheduled demonstrations at three different air shows. They did get some revenue in 2025 by selling a service forward to the city of Abu Dhabi, but zero revenue for actual operations–they have no actual operations. They promise that for this year, 2026, with revenue producing flights in the second half of the year.

Joby Aviation did manage to demonstrate the transition maneuver in April of 2025. And in November they made a point to point flight in Dubai, i.e., their test vehicle managed to take off somewhere and land at a different place. The fact that there were press releases for these two human piloted pretty basic capabilities for an air taxi service suggests to me that they are still years away from doing anything that is an actual taxi service (and with three announced designated place to land and take off from it seems more like a rail network with three stations rather than a taxi service–again slippery definitions do indeed slip and slide). And many more years away from a profitable service. But perhaps it is naive of me to think that a profitable business is the goal.

As with many such technology demonstrators the actual business model seems to be getting cities to spend lots of money on a Kabuki theater technology show, to give credit to the city as being technology forward. Investors, meanwhile invest in the air taxi company thinking it is going to be a real transportation business.

But what about personal transport that you own, not an eVTOL taxi service at all,but an eVTOL that you can individually own, hop into whenever you want and fly it anywhere? In October there was a story in the Wall Street Journal: “I Test Drove a Flying Car. Get Ready, They’re Here.” The author of the story spent three days training to be the safety person in a one seat Pivotal Helix (taking orders at $190,000 a piece, though not yet actually delivering them; also take a look at how the vehicles lurch as they go through the pilot commanded transition maneuver). It is a one seater so the only person in the vehicle has to be the safety person in case something fails. He reports:

After three hellish days in a drooling, Dramamine-induced coma, I failed my check ride.

The next month he tried again. This time he had a prescription for the anti-emetic Zofran and a surplus-store flight suit. The flight suit was to collect his vomit and save his clothes. After four more days of training (that is seven total days of training), he qualified and finally took his first flight, and mercifully did not live up to his call sign of “Upchuck Yeager”. $\190,000 to buy the plane, train for seven days, vomit wildly, have to dress in a flight suit, and be restricted to take off and landing and only fly over privately owned agricultural land or water. This is not a consumer product, and this is not a flying car that is here, despite the true believer headline.

Two years ago I ended my review of flying cars with:

Don’t hold your breath. They are not here. They are not coming soon.

Last year I ended my review with:

Nothing has changed. Billions of dollars have been spent on this fantasy of personal flying cars. It is just that, a fantasy, largely fueled by spending by billionaires.

There are a lot of people spending money from all the investments in these companies, and it is a real dream that they want to succeed for many of them. But it is not happening, even at a tiny scale, anytime soon.

Robotics, AI, and Machine Learning

We are peak popular hype in all of robotics, AI, and machine learning. In January 1976, exactly fifty years ago, I started work on a Masters in machine learning. I have seen a lot of hype and crash cycles in all aspects of AI and robotics, but this time around is the craziest. Perhaps it is the algorithms themselves that are running all our social media that have contributed to this.

But it does not mean that the hype is justified, or that the results over the next decade will pay back the massive investments that are going in to AI and robotics right now.

The current hype is about two particular technologies, with the assumption that these particular technologies are going to deliver on all the competencies we might ever want. This has been the mode of all the hype cycles that I have witnessed in these last fifty years.