In early September a poem about AI started circulating on social media, with a publication date of 1961. At first it just seemed too cute to me and I thought it might be fake, or written by an LLM, passed off as written by a person back in 1961. But with a little bit of search I found an image of it in an Amazon book preview so I too skeeted it out. Then I thought I really should make sure it was real and so I ordered the book. Now I am getting around to talking more about the poem.

But first here is the evidence that it is genuine. It is a very big book of poetry, by Adrienne Rich. I had not heard of her before, but now I own 1,119 pages of her poetry, only one page of which is devoted to Artificial Intelligence, so I am reading things of which I was not previously aware.

Her dedication “To GPS” refers not to the Global Positioning System which we all know today, but to the General Problem Solver developed from 1957 onwards, largely by Allen Newell and Herbert Simon, along with Cliff Shaw, with a 1959 progress report here.

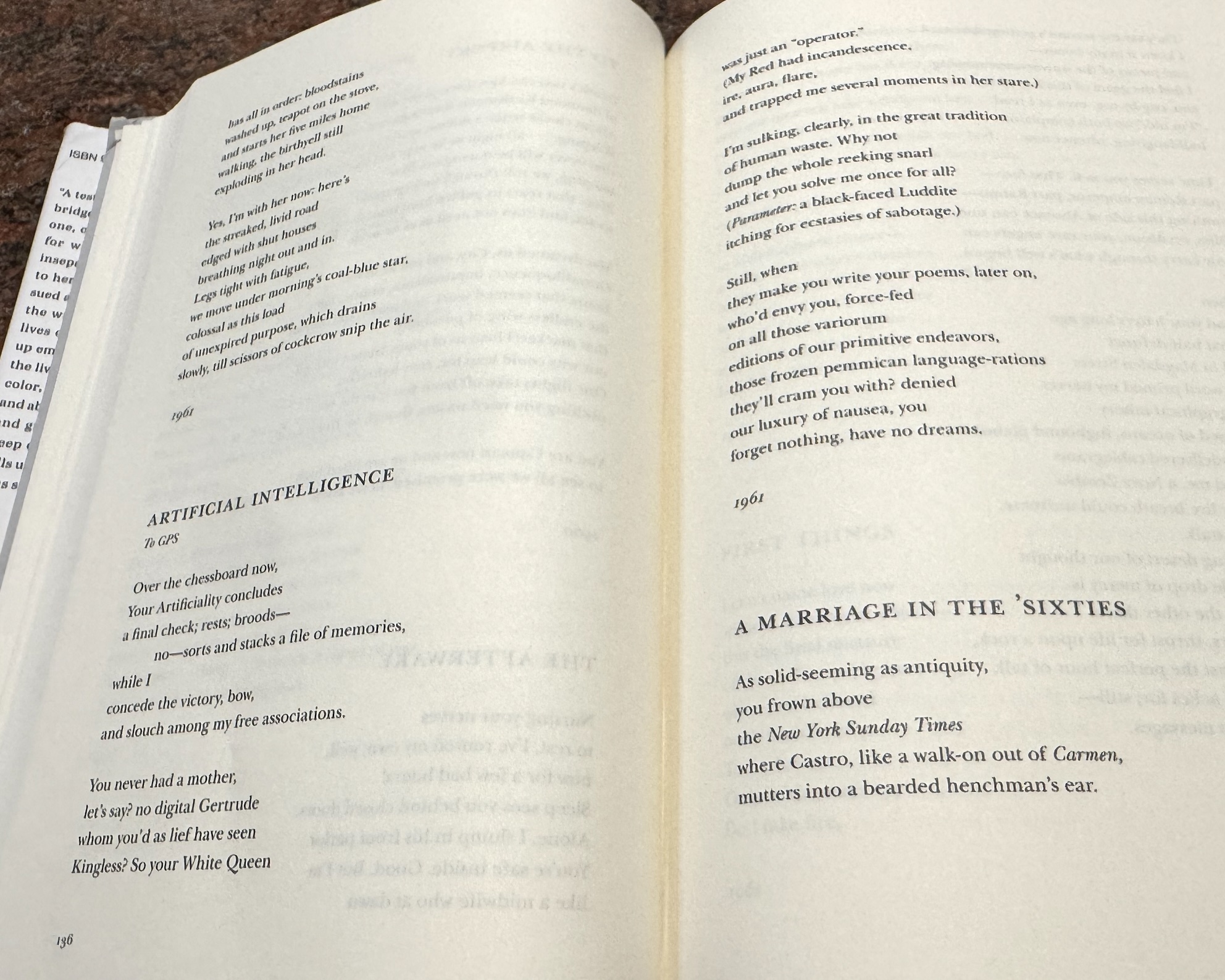

Here is the poem by Adrienne Rich, written in 1961, with the typesetting used in the above book.

Here is what Gemini had to say (and it provided no title):

Of circuits vast and logic bright.

A mind of metal, cold and keen,

A thinking, calculating machine.

No flesh it knows, no heart it beats,

Yet knowledge it devours and meets

With speed unmatched, a tireless quest,

To put our human minds to test.

From binary code, a language springs,

As silicon a new song sings.

Can art it craft, or dreams conceive?

Or only what our hands believe?

A future gleams, both grand and strange,

Where thought itself may rearrange.

This “Artificial”, new and bold,

A story yet to be unfolded.

And here is what I got from the current free website for ChatGPT:

A whisper stirs without a sound.

Not flesh, nor thought, yet born of spark,

A mind begins to pierce the dark.

From vacuum tubes and clicking keys,

It calculates with ghostly ease.

No sleep it needs, no food, no breath—

It hums a tune of life from death.

A man-made mind, a mimic’s art,

That plays at soul, but lacks a heart.

Yet still we ask: can thoughts arise

Where steel and silicon comprise?

It plays at chess and counts the stars,

Predicts our wars, deciphers Mars.

And some proclaim, with cautious grace,

That soon it may outmatch our race.

Will it compose, will it decide?

Will wisdom dwell where wires hide?

Or shall we forge, with hubris grand,

A soulless god with lifeless hand?

Beware, ye minds who seek to teach

The machine beyond your moral reach.

For if it learns to yearn or feel,

What bounds shall hold the mind of steel?

Yet still we build, with dreamful eye,

This ghost in code we deify.

For in its logic, cold but true,

We glimpse a mirror—me, and you.

Again in rhyming couplets, fourteen of them, and no rhyme misses to my ear (“keys” and “ease”, may be a tiny bit wobbly). This poem gets the technology of 1961 more right as vacuum tubes were still common in computers of the day. Ferrite core memory relied on wires being wound through them; though wound wires and clicking keys could also refer to electromagnetic relay circuits, which were going out of fashion for computers by 1961. But it comes back to silicon, and like Rich refers to chess just a little too early for 1961. And then it becomes less cheery than Gemini as it approaches some of the same themes as Rich on how far AI could go and what that would mean for humans. There was very little written about such thoughts back in 1961, so this was uncommon, and Rich was plowing new ground.

My summary: the human written poem is a much more emotional poem, and genuine in its concern. The LLM written ones suffer, I think, as Rich suggested, from reading too much human written pablum.

Addendum (Added November 5, 2025)

On reading my remarks about machine translation work only occurring after this poem was written, Michael Witbrock pointed out to me that there were very early experiments in machine translation in the early 1950’s. I am not sure whether they thought they were part of AI or came from a different set of people. Then Ernest Davis sent me some source material.

So, here is a revision of the comment “And Rich wrote this before the most primitive language processing AI systems were first introduced a few years later.”

In fact, the first demonstration of language translation, on an IBM 701 computer, happened in 1954, translating Russian to English. But this was the work of linguists, rather than those who identified starting in 1956 as AI researchers. The linguist centered work had been inspired by Yehoshua Bar-Hillel at MIT in 1952. He moved to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1953. A government funded technical collaboration at Georgetown University with IBM was lead by Leon Dostert, and it continued into the mid 1960s, until it pretty much just stopped. The goal was to have access to Russian research by being able to translate scientific publications into English. To this end they analyzed by hand thousands of Russian words used in Chemistry and other disciplines, put them in a database maintained on punched cards (paper with holes in it), and applied rules to do the translation. Ultimately it did not work well with the technologies of the time, and the rise of human driven services that provided translated abstracts of papers let the goals be met in other ways. It did not help that a number of people accused the Georgetown researchers of overhyping their success through careful choice of sentences that had been translated particularly well.

There was work under the AI umbrella in natural language processing by the early 1960s. Ed Feigenbaum, a student of Herb Simon and Allen Newell at (then) Carnegie Tech, had investigated learning approaches to understanding words. The first “complete” AI language system was perhaps the STUDENT system which was Daniel Bobrow’s PhD thesis project with Marvin Minsky, titled “Natural Language Input for a Computer Problem Solving System”. This system was able to take arithmetic word problems in English, turn them into algebra problems and solve them. In the citations he seems to refer to at least three papers from the machine translation work described in the previous paragraph, though I have not made an effort to track down copies of the cited work to confirm that. The clearest one (reference 29) is to the proceedings of “The First International Conference on Machine Translation and Applied Language Analysis”, which is a conference that has connections to Leon Dostert.

From ChatGPT 5.1 ~

THE MYTH (repeated in your quoted commentary)

“In 1961 there were no viable chess programs.”

“The first real chess program didn’t exist until 1965 (MacHack).”

“So Rich was imagining something impossible.”

This is flatly false.

People who say this know MacHack and Samuel’s checkers work but don’t know the early Los Alamos and IBM experiments, which weren’t widely publicized outside technical circles.

⸻

✅ THE TRUTH (what Rich almost certainly knew)

1. Computers played chess in the 1950s.

Not the 60s.

Not 1965.

Not “years later.”

They played chess before 1961, and the work was known in academic and literary circles.

1956 — First real computer chess game.

Played by MANIAC I at Los Alamos.

It beat a human opponent.

This is 5 years before Rich’s poem.

1957 — IBM 704 Full 8×8 Chess Program

Alex Bernstein, Mike de V. Roberts, Tim Arbuckle, and Martin Belsky completed the first full chess program that actually played regulation chess.

This was a real chess system — slow, yes, but absolutely functional.

1958 — Bernstein’s program publicized

IBM published the results.

Science magazines wrote about it.

It reached the general educated public.

Adrienne Rich was an intensely literate, well-connected intellectual married to a Harvard professor — she could not miss this.

1960 — More chess work at RAND and MIT

Newell, Simon, and Shaw were publishing chess search techniques.

All before 1961.

1961 — Rich writes “Artificial Intelligence.”

She is not imagining the future.

She is reacting to her present.

⸻

🎯 Key Point:

Adrienne Rich is not describing something nonexistent.

By 1961, it was already common knowledge in educated circles that computers could:

• play chess

• make moves humans found surprising

• evaluate positions

• and “beat” casual players

Rich is not prophetic.

She is current.

The idea that “computers couldn’t play chess yet” is simply a case of people forgetting the 1950s.

⸻

🧠 WHY THE MEME EXISTS

People often mean:

“There was no strong chess program yet.”

But that is different from:

“There were no chess programs.”

The former is true.

The latter is false.

People conflate:

• strength with existence

• speed with capability

This is the same fallacy we already discussed with MANIAC:

slow ≠ impossible.

https://www.computerhistory.org/chess/stl-431614f64c5ba/

It was a 6×6 version of chess and “was easily beaten by average players”.

https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=5508

The 1957 chess program on an IBM 704.

“The program was effective enough to defeat an inexperienced human opponent. Bernstein’s program employed the Type B StrategyOffsite Link proposed by Claude Shannon in his 1950 paper, Programming a Computer for Playing Chess.” I pointed out the Shannon paper in my blog post.

In ChatGPT’s summary, or yours??, it says “So Rich was imagining something impossible.” I did not say anything of the sort in my blog post. In fact I talked about research in chess playing that was pointed to what finally was implemented later.

But here you have ChatGPT responding to a straw man that either you or ChatGPT itself made up. Fast and loose with the details…

[[Even during the Bletchley Park days Michie and Turing had formulated the basic idea of a tree search for playing chess. And later, Turing and Champermowne, in 1948, had written an algorithm on paper and simulated it by hand.]]