The word “robot” has been hijacked. Twice. (Or thrice, if we want to be pedantic, but I won’t be.)

THE ORIGINAL SPIN

The word “robot” was introduced into the English language by the play R.U.R., written in Czech by Karel Capek, and first performed in Prague on January 25, 1921. R.U.R. stands for Rossumovi Univerzálni Roboti, though even in the first edition of the play, according to the play’s Wikipedia page, published by Aventium in Prague in 1920, the cover designed by Karel’s brother Josef Capek, had the English version as the title, Rossum’s Universal Robots, even though the play within was in Czech.

According to Science Friday, the word robot comes from an old Church Slavonic word, robota, meaning “servitude”, “forced labor”, or “drudgery”. And the more you look the more references indicate that it is not known whether Karel or Josef suggested the word.

But, in any case, in the play the robots were not electro-mechanical devices, in the way I have used the word robot all my life, in agreement with encyclopedias and Wikipedia. Instead they were “living flesh and blood creatures”, made from an artificial protoplasm. They “may be mistaken for humans and can think for themselves”. Both quotations here are from the Wikipedia page about the play, linked to above. According to Science Friday they “lack nothing but a soul”.

This is the common story, more or less, about where the word robot came from.

<aside>

But, but, maybe not. According to this report the word “robot” first appeared in English in 1839. 1839! It says that robot at that time referred not to an individual, neither machine, nor protoplasm, nor electro-mechanical , but rather to a system, a “central European system of serfdom, by which a tenant’s rent was paid in forced labour or service”. Ultimately that word came from the same Slavonic root.

So perhaps in English the word “robot” changed in meaning between 1839 and 1920. Though realistically perhaps no one who picked it up from the Capek brothers in 1920 had ever heard of it from the old 1839 meaning. And in any case it seems such a different use that I don’t think it really is a hijacking. Just as “field” was not “hijacked” in going from a field of wheat to a field of study.

I am not going to count this as a “robot” hijacking.

</aside>

In 1920 “robot” referred to humans without souls, manufactured from protoplasm. But that meaning changed quickly.

THE FIRST HIJACKING

By the time I was deciding what really interested me in life, the word “robot” had turned into meaning a machine, as given by the online English Oxford Living Dictionaries, where it defines the word as:

A machine capable of carrying out a complex series of actions automatically, especially one programmable by a computer.

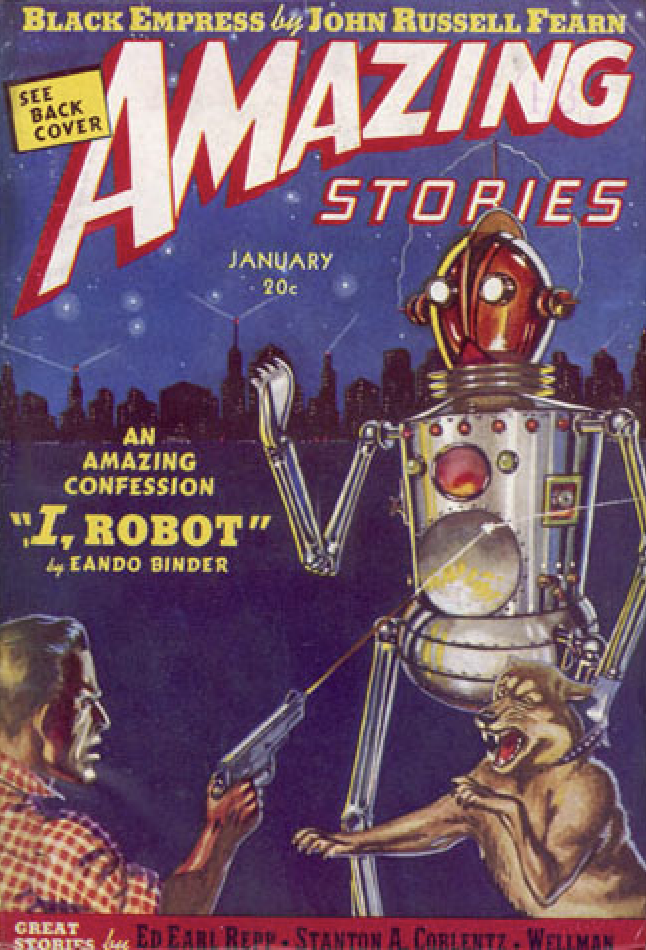

Here is the cover of the January 1939 edition of Amazing Stories.

There is a robot, a machine, right on the cover, illustrating a story titled I, Robot. But for me the big news is that the author of that story is Eando Binder (a nom de plume for Earl and Otto Binder), rather than Isaac Asimov–we’ll get back to Dr. Asimov in just a minute. I have found one slightly earlier reference to mechanical robots, but it is only a passing reference. In this Wikipedia list of fictional robots there is a story titled Robots Return, by Robot Moore Williams, dated 1938. Unfortunately I do not have the text of either of the 1938 or 1939 stories, so can’t tell whether the authors assume that their readers implicitly understand to what the word “robot” refers.

However, in 1940, only twenty years after the R.U.R. play was first published with the English version of robot on its cover, Isaac Asimov published his story Strange Playfellow in Super Science Stories, an American pulp science fiction magazine (of the Binder story he said “It certainly caught my attention” and that he started work on his story two months later). Later, retitled as Robbie, the story was the first one that appeared in Asimov’s collection of stories published as the book I, Robot, on December 2, 1950. I have a 1975 reprint of a republished version of that book from 1968. In that reprint, at the bottom of the third page, after describing a little girl, Gloria, playing with a mechanical humanoid Robbie, Asimov uses the word “robot” to refer to Robbie (note the alliteration) in a very casual way, as though the reader should know the word robot. The word “robot” got hijacked in just 20 years, in the popular culture, or at least in the science fiction popular culture, from meaning a humanoid made of protoplasm in a Czech language play in Prague, to meaning a machine that could walk, play with, and communicate with humans. Note that 1940 was before programmable computers existed, so there was some more evolution to get to the definition involving computers as quoted above.

In the 1920’s such mechanical humanoids seem to have been referred to as “automatons”.

I have no idea what contributed to that transformation of the word “robot”, but I am eager to see any citations that might be offered in the comments section.

So now we have the first real hijacking of “robot”. But there has been a more recent one. I may not care deeply about the earlier hijacking, but I sure do care about this one. I am an old school roboticist in the sense of the definition in italics four paragraphs back. And my meaning has been hijacked!!

THE SECOND HIJACKING

In the more recent hijacking, “robot” has come to mean some sort of mindless software program, that does things that are relentless, or sometimes even cruel, though sometimes amusing and helpful. This new use is getting so bad that it is often hard to tell from a headline with the word “robot” to which form of robot the story refers. And I think it is giving electromechanical robots, my life’s work, a bad name.

I think it starts with this secondary definition which also appears with the English Oxford Living Dictionaries definition from above.

Used to refer to a person who behaves in a mechanical or unemotional manner.

And then it includes an example of usage: ‘public servants are not expected to be mindless robots’.

Now Asimov’s robots have not been mindless, and none of mine have ever been mindless (well, perhaps my insect-based robots were a little mindless, certainly not conscious in any way). But the first industrial robots introduced into a GM automobile plant in 1961 certainly were mindless. They did the same thing over and over, without sensing the world, and did not care whether or not the parts or sheet metal they were operating on was even there. And woe be a person who got in their way. They had no idea there was someone there, and even had no idea that someone, or anyone for that matter, existed, or even could exist. They did not have computers controlling them.

I may be wrong, but I trace the hijacking of the word “robot” to two things that happened in 1994. I am guessing that there is some earlier history, but that I am just not aware of it. Ultimately it is all the fault of the World Wide Web…

Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web and put up the first Web page in 1991. Explosive growth in the Web started soon after, and by 1994 there were multiple attempts to automatically index the whole Web. Today we use Google or Bing, but 1994 was well before either of those existed. The way today’s search engines, and those of 1994, know what is out on the Web is that they work in the background building a constantly updated index. Whenever someone searches for something it is compared to the current state of the index, and that is what is actually searched right then and there–not all the Web pages spread all over the world. But the program that does search all those pages in the background is known as a Web Crawler.

By 1994 some people wanted to stop Web Crawlers from indexing their site, and a convention came about to put a file named robots.txt in the root directory of a web site. That file would never be noticed by Web browsers, but a politely written Web Crawler would read it and see if it was forbidden from indexing the site, or if it was to stay away from particular parts of the site, or how often the owner of the site thought it reasonable to be crawled. The contents of such a file follow the robots exclusion standard of which an early version was established in February 1994.

You can see a list of 302 known Web Crawlers (listed as a “Robots Database”!) currently active (I was surprised that there are so many!). Of the 302 Web Crawlers, 29 include “robot” in their name (including “Robbie the Robot”), 18 include “bot” (including “Googlebot”), three have “robo”, and one has “robi”. Web Crawlers, which are not physical robots, have certainly taken on “robot” as part of their identity. Web Crawlers became “robots”, I guess, for their mindless search of the Web, indexing it all, and following every link without understanding what was there.

That same year there was another innovation. There had been programs, all the way back to the sixties, that could engage in forms of back and forth typed language with humans. In 1994 they got a new name, chatterbots, or chat bots, and some of them had a more or less permanent existence on particular Web pages. Probably they attracted the suffix “bot”, as they could seem rather mindless and repetitive, again harking back to the dictionary example above of mindlessness of robots.

Now we had both Web Crawlers and programs that could converse (mostly badly) in English that had taken parts of their class names from the word “robot”. Neither were independent machines. They were just software. Robots had gone from protoplasm, to electromechanical, to purely software. While no one is really building machines from protoplasm, some of us are building electromechanical devices that are quite useful in the world. Our robots are not just programs.

Since 1994 the situation has only gotten worse! “Robo”, “bot” and “robot” have been used for more and more sorts of programs. In a 2011 article, Erin McKean pointed out that there were “robo” prefixes, and “bot” suffixes, and that at that time, in general, robo has a slightly more sinister meaning than bot. There was “Robocop”, definitely sinister, and there were annoying “robocalls” to our phones, “robo-trading” in stocks caused the 2010 “Flash Crash” of the markets, and “robo-signers” were people signing foreclosure documents in the mortgage crisis. Chat bots, twitter bots, etc., could be annoying, but were not sinister.

Now both sides are bad. We see malicious chat bots filling chat rooms intended for humans, we see “botnets” of zombie computers, taken over by hackers to launch massive denials of service on people or companies or governments all over the world.

Here is a list of varieties of bots, all software entities. Some good, some bad.

At some web sites, such as topbots.com, it seems to be all about “bots”, but it is hard to tell which ones are software or if any have a hardware component at all. Now “bots” seems to have become a generalized word for all aspects of A.I., deep learning, big data, and IoT. It is sucking all up before it.

The word “robot” and its components have been taken to new meanings in the last twenty or so years.

A NEW WORD FOR ELECTROMECHANICAL ROBOTS?

Here’s the bottom line. My version of the word “robot” has been hijacked. And since that is how I define myself, a guy who builds robots (according to my definition) this is of great concern. I don’t think we can ever reclaim the word robot (no more so than reclaim the word “hacker”, which used to be only pristine goodness forty years ago, and I was honored when anyone ever referred to me as a hacker, even more so as a “robot hacker”). I think the only thing to do is to replace it.

How about a new word? What should we call good old fashioned robots? GOFR perhaps?

One that comes to mind is “droid”, a shortened version of “android”, which before it was a phone software system meant a robot with a human appearance. Droid distinguishes itself from the hijacked version of android which refers to phone software, and is generally understood by people to mean an electromechanical entity, an old style robot. Star Wars is largely responsible for that general perception. But that is also the problem in trying to use the word more generally. The Star Wars franchise has the word “droid” completely bottled up and copyrighted. I know of three robot start up companies that wanted to use the word “droid”, and all three gave up in the face of legal problems in trying to do that.

No droids. Unfortunately.

So…what should the new word be? Put your suggestions in the comment section![]() , and let’s see what we can come up with!

, and let’s see what we can come up with!

![]() I manually filter all comments, as the majority of comments posted are actually advertisements for male erectile dysfunction drugs…

I manually filter all comments, as the majority of comments posted are actually advertisements for male erectile dysfunction drugs…

The Chinese word for robot, 機器人, is literally translated as machine-person or ‘mechanical person’. Maybe we just need to be more explicit in our language rather than inventing a new word.

Or ‘mech’ for short?

And the French word for a human-like robot is “un androïde”, but because of the confusion with the Google OS, I hear it more and more being replaced with the expression “un robot humanoïde”, sometimes shortened as “un humonoïde” (a humanoid). Not sure if this helps the discussion, but there you go…

Throwing some out there.

Autobot

Automoton

Actubot

Ibot

Bodybot

Phybot

Mechai

Robun

Sensors, Motors = Semors.

Xobot

Such an important quest. Not GOFR but GOFER (Good Old Fashioned Electromechanical Robot) in honor of John Haugeland.

Thanks Alan! I like the added “E”!! And yes, a nod to John Haugeland was certainly my sly intent.

For a long time I’ve extended his GOFAI to GOFAIR to refer to traditional horizontal robot architectures with three boxes: Perception->Reason/Plan->Act, as contrasted with vertical Albus/Brooks/subsumption/layered control.

Here’s another data point for you: ever since my childhood in the early 80’s, I’ve understood “robot” to mean “a machine, capable of taking action in the world, that is controlled by a computer”. In other words, the presence of the computer was the key element of a robot. By that definition, a “robot” could be a Nao, a Roomba, or even a coffee maker, depending on how sophisticated it is. I always took this to be the root of the software-only sense of “robot” or “bot”; while they might not have local electro-mechanical bodies, bots do actuate and affect the state of the world. The Flash Crash trade-bots of 2010 demonstrated that. Therefore, I take “bot” to refer to a software program that has agency- some degree of independence, goals, or decision-making capability.

As for personal identity, “roboticist” may seem pretentious, but it has so far avoided corruption. A programmer who only makes software robots is still not considered a roboticist.

Rod, I think much worse is the use of “robot” for what is really a waldo — something remotely controlled rather than autonomous. At least these non-physical agents, ‘bots’, are somewhat autonomous.

Yes, that has worried me too. Though I was guilty of it at iRobot, where some of the military robots, now spun out to Endeavor Robotics, were used in a waldo mode. Though over time they got more autonomy to do things like right themselves when they fell down a ditch, or even to find their way back home when they lots communications.

I quite agree that applying the word “robot” to a teleoperated machine is the worst kind of hijacking. The machine has the appearance of a robot, but, like Oz, there is a man behind the curtain. This confuses the public and dilutes the word “robot” in to homeopathic meaninglessness.

Rodney, I think we need more specifity, robot is already an overloaded term.

Homeostatic Andi – chatbot

Cybert – artificial persona, human facing interface

Embodied mind – Sally embody

Neurotic Net – a positronic brain

Grey Waldos – remote controlled waldonic ala ‘Robot Wars’

Norman Normind – unthinking beurocrat such as banking creditworthiness algo.

Algenon Algotron – human who identifies as robotic

Johnny Jargon – an AI that hides human failings by accepting the blame for PEBCAC

most simple translation of robota (no matter if it’s czech, slovak, etc…) is WORK. So robot is something that does work instead of human..

How about the term used in anime subculture: mech

Aaron Edsinger named his company “Meka”, which I really liked. He built upper torso humanoids for the research market, until he was bought by Google.

Meka have a long history and a specific meaning in Japan, so I think it’s too late to appropriate that word. But I like the way the Japanese use it, for a machine that can be piloted but can also operate with limited autonomy.

Golems are robots in some archaic sense. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golem

The other hijacked word is “computer” – which used to refer to people who calculated, perhaps using devices like slide rules, if I recall right.

For robots, a phrase to capture the essence of GOFR would be useful – perhaps “embodied computer programs”?

“emgram” doesn’t work (close cousin of n-gram).

Just “em” would’ve worked, but it’s taken by Robin Hanson (book – The Age of Em) where it refers to “brain emulation” – programs that may optionally be embodied and are created by scanning the brain state and architecture of some human. Maybe we can hijack “em” from Hanson 🙂

The women in “Hidden Figures” were called “computers”, and this was a common term. They did not use slide rules, which are limited to 2 to 3 decimal digits at each step, as human computers usually did long complex calculations to many decimal places. The had pencils, paper, and sometimes mechanical adding machines. Turing’s 1936 paper on computable numbers uses a human computer, “a man in the process of computing a real number”, as his model for a machine computing a real number, following prescribed steps with decision points, and recording results by putting marks on paper.

In South African English, a “robot” is short for “robot policeman” and means a traffic light. http://boards.straightdope.com/sdmb/showthread.php?t=387828 quotes the OED citation “Even. Standard 5 Aug. 2/1 (heading) Traffic ‘Robots’ in the City.” A further search for that London Evening Standard citation finds https://books.google.se/books?id=4djICT7zgGoC&lpg=PA201&ots=zXP4eNUfoF&dq=%22Traffic%20%E2%80%98Robots%E2%80%99%20in%20the%20City%22&hl=sv&pg=PA201#v=onepage&q=%22Traffic%20%E2%80%98Robots%E2%80%99%20in%20the%20City%22&f=false which says that already by 1927 an American newspaper was talking about “electrical robots”. I couldn’t find that newspaper, but using “electrical robot” as the marker of the first hijack, I did find an October 27, 1928 article in The Register, Adelaide at http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/56762327 with the text “the electrical Robot man, almost the realization of a Wellsian-cum-Jules Verne dream (writes a correspondent in The Observer, London).”

A search of the archive of The Guardian / The Observer at http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/guardian/advancedsearch.html finds titles like ‘THE “ROBOT” OFFICE’ (1926), ‘THE “ROBOT” M.P.’S.’ (1927), ‘THE MECHANICAL MAN’ (1927), ‘A LAWN ‘TENNIS “ROBOT.”‘ (1927), ‘ROBOT RAILWAY’ (1928), and more. It’s apparently free to read the articles if you sign up for an account.

It makes me think the transition from protoplasm to electro-mechanical robots was almost immediate.

Wow! That really is immediate. You have nailed it that it had happened by 1926–1928. And I certainly did not expect the evidence trail to go via Adelaide (my home town), though that story is about something in London.

There’s a Punch cartoon from 1927, captioned ‘Hoist With His Own Roboot’, that appears to show a mechanical robot: http://punch.photoshelter.com/image/I0000hkhKFoO4I5E

This is certainly interesting for 1927! The “robot” has “SOVIET” written on it, and it is giving the boot (literally) to someone. The sub caption says “Why did I help to make this machine so efficient?”. That could be referring to the party/revolution, as a machine. And it could, conceivably, be using the soul-less protoplasm version of the word “robot” to refer to a party member. BUT the drawing looks like the “robot” is a machine, at the joints of the limbs, and especically in the expose knee that is doing the kicking. The keyword list below includes “Leon Trotsky” and “Josef Stalin”, so I assume from the appearances, and the date of 1927, that the robot is Stalin, and the one getting kicked is Trotsky. Trotsky was removed from power in October 1927 having earlier fallen out with Stalin.

So I wonder whether a “robot” as a mechanical entity was already a trope, or whether there was an R.U.R. connection to how people in the West viewed the treatment of workers in the Communist Party, and whether this was a transition image. Any early Soviet scholars with some clues?

#### Oops, now that I see Andrew Dalke’s comment and his references to newspapers usage of the word “robot” as a mechanical humanoid from 1926–1928, this cartoon clearly must be of a mechanical version of Stalin.

My personal inclination is to try to reclaim the word “robot”, by aggressively asserting that a robot must sense and act in a “real” world, with some sort of representation and decision process in between (most likely structured as an Albus/Brooks hierarchy of feedback loops, rather than a single straight-forward sense-plan-act loop). I put “real” in scare-quotes because a simulated robot like SHRDLU functions in a simulated world, but still deserves to be called a robot. Excluded from the term “robot” are waldos, which can be very useful, but can also be dismissed as “remote-control toys”. Likewise excluded are traditional industrial robot manipulators, since they don’t sense, or build representations, or respond to those representations in any way. But they get to keep using the word since there are a lot of them, and they have been calling their machines by that word for decades.

This can require the term “physical robot” when you want to emphasize that the robot is embedded in the physical world, not just a simulated world. It makes sense that “physical” would be the default for “robot”, with some “bots” (or “robo-“s) being software robots in digital worlds, while others are just metaphorical extensions of the term. Within physical robots, “electro-mechanical” is a pretty strong default, since there are very few hydraulic or pneumatic robots.

The cool thing about working on physical robots is that you need to confront the unbounded complexity of the physical world (not to mention doing things to help people, since we live in the physical world AFAIK). Simulated worlds (like SHRDLU’s) are necessarily far simpler. A digital “world” like the Internet is pretty complex, but I’d say many orders of magnitude less so than the physical world.

Boundary cases like traditional thermostats or early Roombas meet the definition for “robots”, but their representations are pretty degenerate (like asking whether a low-level insect has a “mind” — yes, but . . . ).

Anyway, I’m for sticking with “robot”, and working to clarify that that means sensing and acting in a world, and using some sort of representation in between.

Thanks Ben, thoughtful as always. “Physical robot” might be a good interim solution.

Gotta watch out for IoT being called a robot if physical sensing and action is all that is required.

Artificial Human Companions!

Hi Simon, I’m really not as despondent about progress as your blog post under your name suggests.

Great to hear that! I’m not either; embodied intelligence is definitely the way to go. Your work has been remarkable.

Simon

Companion has all the right meanings.

Not always friend, but not an enemy.

Working together, working alongside.

Moving in the same direction or with the same purpose.

Companion is flexible enough that we use it to mean non-humans like our pets or working animals like horses.

Companion is a great word – we could use ‘Comps’ as the short form which can be interpreted in complimentary ways – Computational or/and Companion.

Meanwhile some guy named Baxter is trying to prove he is indeed human.

Bots, drones, iot, hackers – these terms do get appropriated as you mention but once a robot is built it becomes a Baxter, a Roomba, etc.

The term ‘robotics’ does not seem to suffer from this problem.

When I was in college, I read a novelette by Anatoly Dnieprov, one of the early Soviet science fiction writers. The robot in the story was named Siema. The name had a specific meaning or acronym that I can’t recall. In Russian, it’s Суэма, which may indicate a derivation from cybernetics, which comes from the Greek κυβερ, “to steer”.

Anyway, even though it sounds a bit like Siri, perhaps we could called them Siema. It’s both singular and plural, which has some advantages when referring to hive robots.

Hello Rodney (if I may),

Thanks for the very interesting post, it’s important a person like you indicates words are one of the lens through which we co-create our (technological) reality, shape our opportunities or cognitive deadlocks. I agree for example that the underground historical relationship between the word robot and the ideas of communism or socialism is underestimated.

Instead of coining a new word, we could use an old but evolutive historical term that we have had to handle in the past. I have a proposition below, and it’s not “slave”.

I was thinking about your post this morning (I read it a few days ago but had then no alternative word to propose), since I am about to give (tomorrow) a lecture at KTH Sweden on the perspective I have taken to calling “anthrobotics”, which looks at the collective and historical aspect of social automata (which are always a compound of flesh and algorithmic routines).

English already has a convenient word used to describe humans that are supposed to work more or less selflessly and embody a superstructural social machine, social order or institution: “servants” — as in “civil servants” for example. A servant is defined as “a person who performs duties for others…” Today, servant is a more or less old-fashioned word that implies a specific social system. Some might think it’s offensive for humans. If we can’t easily apply “servant” to humans anymore, or if we follow the utopia according to which no human should be a servant (or if we notice how difficult it has become for global individualist consumers to be serving and selfless citizens), why not recycle the word servant to describe droids and humanoid robots?

Note the term “duty” in the above definition. Duty is one of the 4 agentic drives in organised groups I have identified in my PhD and in the paper “We, anthrobot: Learning From Human Forms of Interaction and Esprit de Corps to Develop More Plural Social Robotics”. If we redefine droid robots as servants, this would perhaps change our perception and design of machines (and of future humans). Robots and droids would be but a new phase of the long and multifarious history of servants.

Best wishes,

Luis

Hmmm. I see the logic to this suggestion. I am not sure how socially acceptable it would feel in use, however. Pondering…

Controller – Just as “computer” now means an artificial system that performs computation once carried out by humans, I propose “Controller” as the term for an artificial system that embodies the process of perceptual control.

I agree with your desire for a new word, as “robot” is too, err, robotic, and have been giving it some thought for a while. The background is explained in my imminent paper (inspired by your own work), for details see http://www.perceptualrobots.com/controller/.

Just a very rough thought, riffing on Simon’s suggestion:

auphma – AUtonomous PHysical MAchine

I’m guessing the next common name could be defined by the name given to the next robotic commercial success. A “Kleenex” phenomenon. A name doesn’t have to have an innate meaning to be successful, it merely needs to be distinct and widely accepted.